Guest Post by Ana María Pérez-Hincapié, 2024-2025 Sustainability Leadership Fellow and Ph.D. Student in the Department of Geosciences at Colorado State University

What comes to your mind when we think of landscapes? Maybe some of us think of natural parks or our last summer getaway on a beautiful scenic driveway. It is impossible not to be amazed by how breathtaking some places can be or not to feel nostalgic when we remember the mountains of the place we call home. Despite being present in our daily lives, we rarely pause and think that what we see around us is the product of thousands or millions of years, of immense processes that create and destroy mountains, of waves and rivers that sculpt with infinite patience what we inhabit.

The concept of geological time can create the illusion that we live in a static world, on a fixed rock that simply exist for our development. When it is a dynamic planet in constant transformation. Therefore, it is not surprising that as our production models become more demanding and as the planet’s population migrates to cities, conflicts with the dynamics of our planet’s surface become more apparent. One of the clearest ways these conflicts manifest is through natural hazards. Although these events can be tremendously disruptive and take many lives, they are sometimes reduced to numbers and probabilities, which prevents us from reading the signs present in the territory.

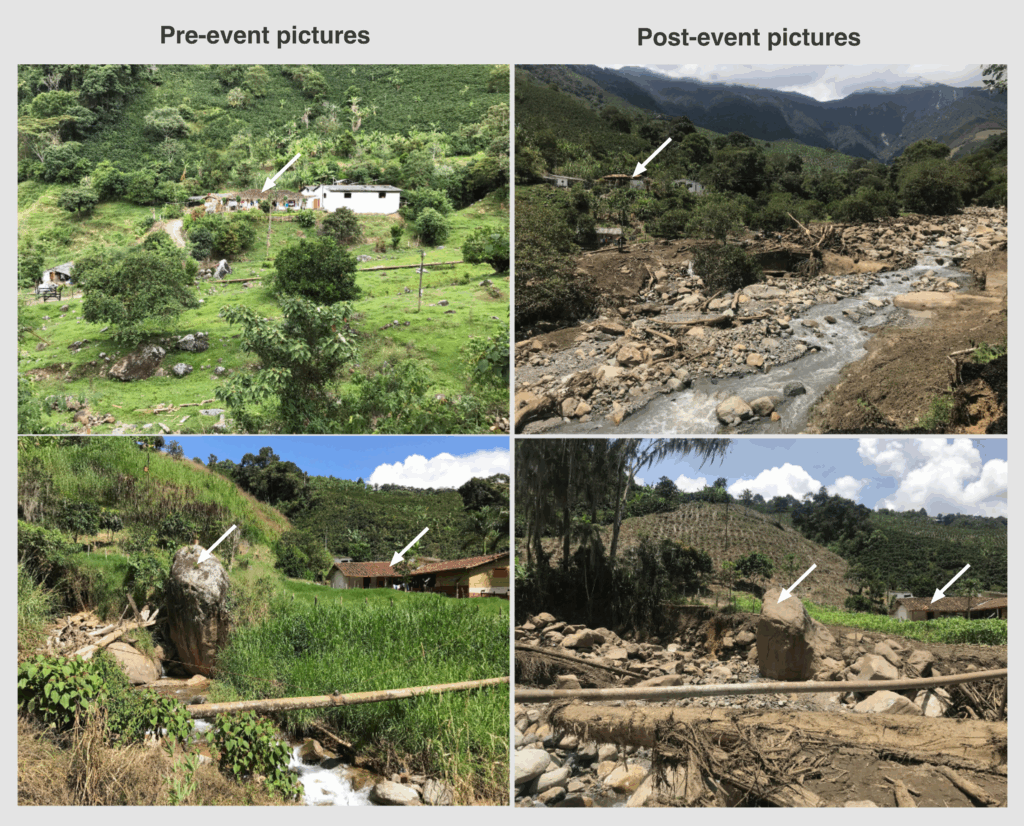

Next time you’re near a river, take a moment to observe the rocks. Some are massive, far larger than what we might expect from a calm stream. These stones are silent witnesses to the river’s past power, a reminder that high-energy events capable of moving such sediment have occurred and, will likely occur again. While we tend to think of natural disasters like volcanic eruptions, floods, or earthquakes as isolated incidents, they are in fact part of Earth’s continuous transformation. Their future behavior is not only shaped by long-standing geological processes but also increasingly by human intervention and climate change.

Understanding the land we inhabit goes far beyond scientific curiosity. In recent years we have had painful examples of how these conflicts with the earth surface dynamics translate into loss of life and a fiscal cost that exceeds the possibilities of any country. Hurricane Katrina in 2005 remains in the minds of many Americans, with a death toll in the hundreds and financial losses estimated at USD $125 billion (or up to USD $202.5 billion adjusted for 2025 Consumer price index1). While disasters of this scale are always the result of many contributing factors, they also reflect the friction between cities and the landscapes they occupy. Consider the Mississippi Delta, a region in constant flux within one of the world’s largest river basins. Here, flooding isn’t just a threat, it’s part of the natural cycle, one that now coexists with increasingly intense hurricane seasons driven by a warming atmosphere and ocean.

Although these large-scale disasters are extremely damaging and remain in our collective memory, it’s also crucial to recognize the smaller, more frequent events that may seem insignificant on their own but add up to substantial impact when added together. These events often tend to represent an important percentage of the Gross Domestic Product – GDP of entire countries. With a particularly devastating effect in developing nations, often increasing social problems that exacerbate inequality.

There we cannot talk about long-term sustainability without acknowledging the constraints and the opportunities of the land we live on. This is both a challenge and an invitation. It is clear that we cannot resettle entire cities or restart society from scratch. And that on many cases the landscape has deeply shaped the culture, and we want to preserve it. But in a world facing climate change and increasing vulnerability to hazards, stronger efforts are needed to align urbanization and development with the landscape’s dynamics.

Even when we feel powerless, there’s a key concept that helps clarify what is within our control and what lies beyond it: geological risk. It’s not just about the natural hazard itself, but about how that hazard intersects with our exposure and vulnerability. This is where meaningful action begins, not only from governments but also from communities and private companies. While we cannot predict earthquakes or volcanic eruptions, we can learn to read our landscape, understand its past behavior, and make plans so our infrastructure and interventions are prepared for what we cannot control. Vulnerability goes beyond buildings and constructions, it integrates social preparedness, knowledge, and financial safety nets that help us recover more effectively.

There are still many challenges to reducing our vulnerability and improving our resilience. For instance, the wildfires in Los Angeles in January 2025 highlighted the need to rethink insurance models and business strategies so that hydrometeorological events don’t become sources of asset loss that deepen inequality. Ultimately, our future, and the sustainability we aspire to, depends on how well we learn to adapt to the rhythms of a landscape that has been signaling us far more than we’ve learned to listen.

References:

- https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/billions/dcmi.pdf