Guest Post by Michelan Wilson, 2022-2023 Sustainability Leadership Fellow, and Ph.D. Candidate in the Department of Economics at Colorado State University

As we head into the 27th United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP27), issues surrounding the impact of climate change in the Caribbean are high on the agenda. The conference has been held annually since 1992 and governments use it to agree on actions to limit global temperature increases associated with climate change. This year, Caribbean leaders will use the conference to collectively advocate for loss and damage compensation for the impacts of climate change. Caribbean leaders will travel to Egypt to lobby for climate justice for their islands by pushing developed countries to create a funding facility to pay for the climate change consequences that exceed what these nations can adapt. In doing so, develop nations will acknowledge that the region is more vulnerable to climate change and mitigation and adaptation financing should not be left to just us, as Caribbean islands.

According to the US EPA, environmental justice is “the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people, regardless of race, color, national origin, or income, with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies”. This implies that no group should be disproportionately impacted by the negative environmental consequences of policies. Climate justice is a category of environmental justice and recognizes that climate change impacts are not distributed or experienced equally, and as such, can exacerbate inequitable social conditions within and between countries. We see this in all countries where people of color, indigenous groups and the socially disadvantaged are more negatively impacted by climate-related disasters. So why is the Caribbean Community making such a big fuss?

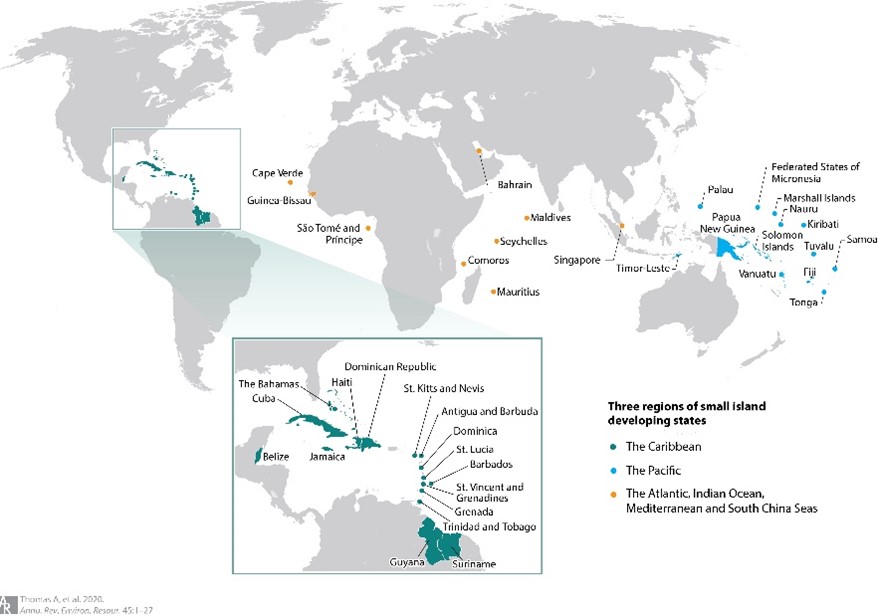

Caribbean nations are a part of the 58 small island developing states (SIDS) that are on the frontlines of climate change (see Figure 1). SIDS make up about 1% of the world’s population and face similar economic, social and environmental challenges due to factors including their geographical location, reliance on natural resources and limited industrial activities (Thomas, 2020). Most SIDS have made a very small contribution to the overall global emissions that cause climate change, contributing less than 1% of global carbon emissions (Mead, 2021) yet are the most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. SIDS face a range of risks, including extreme floods, storms, droughts, unpredictability of precipitation patterns and sea-level rise, ocean acidification and deoxygenation (World Health Organization, 2018; Douglas & Cooper, 2020, Thomas, 2020). These effects of climate change have been closely linked to socioecological hazards, including biodiversity loss, pollution, deforestation, coastal erosion, overfishing, and freshwater salinization (Douglas & Cooper, 2020). The problem for SIDS is that they have a significantly higher proportion of their population and physical assets located in areas of high exposure to climate change. Most SIDS are in the tropics and subtropics and have large portions of populations, infrastructure, and assets located along the coast, guaranteeing maximum exposure to climate change (Thomas, 2020). Remarkably, these characteristics make SIDS unique, but at the same time they make them the most vulnerable to climate change.

As small islands, the sectors that are most important for economic output include, tourism, fisheries and agriculture. These sectors heavily rely on the state of the environment and are therefore affected by environmental change. For example, in 2017, Puerto Rico was hit by hurricane Irma and Maria. The total loss in the agricultural sector (production and infrastructure) was estimated to be upwards of US$ 2 billion. This loss in agricultural production as well as other hurricane-related import restrictions led to issues of food insecurity on the island (Álvarez-Berríos et al., 2021). Overall, Hurricanes Irma and Maria caused losses totaling US$ 42 billion across the Caribbean (Álvarez-Berríos et al., 2021). Outside of agriculture, approximately 20% of GDP comes from coastal-based tourism in over 50% of SIDS, with this percentage increasing to 50% for tourism dependent islands (Thomas, 2020). Coral reef degradation, coastal erosions, increases in temperature and other climate-related impacts are estimated to reduce tourism revenues by approximately US$118 million–US$146 million per annum (Moore, 2010), on average, across the Caribbean. Marine loss in the subtropical zone (30o N – 30o S) are expected to reach 7–9% of GDP by 2050 in SIDS. While economic losses are associated with climate change for all countries, the losses for SIDS are higher than the global average. In the Caribbean, economic losses due to climate change are expected to rise from 5% of GDP in 2025 to 20% of GDP in 2100, if no adaptation or mitigation action is taken (Thomas, 2020). This disparity in the impact of climate change is also seen within countries, where we find that individuals that are more dependent on natural resources and female-headed households within SIDS are more negatively impacted by climate change (Shah, 203). Given the reliance on these sectors, the losses due to climate change are expected to disproportionately affect the livelihoods of people living in the Caribbean. So why don’t these islands just adapt to climate change?

These islands simply do not have the money to adapt! Many national governments in SIDS are unable to devote sufficient personnel and funds to climate change adaptation and face data constraints that limit their ability to plan appropriate responses to the impacts of climate-related environmental change (Thomas, 2020). Additionally, adaptation projects are usually short-lived as SIDS oftentimes must re-divert funds from adaptation or development projects to address extreme events. SIDS also heavily rely on supplemental assistance from other countries and international organizations (Thomas, 2020). This highlights another constraint for SIDS; capacity constraints lead to funds being diverted from sustainable development projects, but unsustainable development increases the vulnerability of SIDS to climate change. As such, there is a need for climate financing, and this should be the topic of discussion at COP27.

During COP15 in 2005, developed countries pledged to donate US$ 100 billion per year for climate mitigation and adaptation in developing countries by 2020. In 2020, developed countries contributed only US$ 83.3 billion of the US$ 100 billion annual commitment, the highest since 2005, and have essentially gone back on their promises (OECD, 2022). Even more disheartening, SIDS were only allowed access to US$ 1.5 billion of the US$ 100 billion (Akiwumi, 2022), despite being some of the countries hardest hit by climate change. This is due to criteria for allocating funds and is just one of the constraints faced by SIDS when accessing climate financing. Funds are allocated based on GDP per capita rather than vulnerability. This means that SIDS that are identified as middle-income countries based on GDP per capita have limited access to climate mitigation and adaptation funding, despite facing greater negative impacts while having very low contribution to climate change. Instead, higher income SIDS are granted access only after a disaster. For those SIDS that meet the threshold requirement, they are further constrained by their human and technical capacity to meet donors’ proposal standards and reporting requirements. SIDS are further constrained by competition with larger developing countries for project financing. This one-size-fits-all policy for accessing climate financing does not prioritize countries most vulnerable to climate change impacts. These are just some of the injustices that need to be addressed at COP27.

Global climate policy must be such that it does not exacerbate the already existing inequities between countries. In fact, climate policy should focus on correcting these injustices. We must recognize SIDS are more vulnerable to climate change impacts and are less flexible in their response and as such, face more devastating disruptions to livelihoods, landscapes, and ecologies than developed countries. Caribbean islands should not be forced to choose between climate adaptation and mitigation and development but should instead be afforded the same development opportunities as current developed countries. COP27 needs to be about seeking justice for the Caribbean, as it is not just us who should be held responsible for climate change financing.

Sources Cited:

Álvarez-Berríos, N. L., Wiener, S. L., McGinley, K. A., Lindsey, A. B., & Gould, W. A. (2021). Hurricane effects, mitigation, and preparedness in the Caribbean: Perspectives on high importance-low prevalence practices from agricultural advisors. Journal of emergency management, 19(8).

Climate Finance Access Network. (n.d). Accessing Climate Finance: Challenges and opportunities for Small Island Developing States. United Nations Report.

Douglass, K., & Cooper, J. (2020). Archaeology, environmental justice, and climate change on islands of the Caribbean and southwestern Indian Ocean. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(15), 8254-8262.

Mead, L. (2021). Small Islands, Large Oceans: Voices on the Frontlines of Climate Change.

Moore, W. R. (2010). The impact of climate change on Caribbean tourism demand. Current Issues in Tourism, 13(5), 495-505.

OECD (2022). Aggregate Trends of Climate Finance Provided and Mobilised by Developed Countries in 2013-2020

Shah, K. U., Dulal, H. B., Johnson, C., & Baptiste, A. (2013). Understanding livelihood vulnerability to climate change: Applying the livelihood vulnerability index in Trinidad and Tobago. Geoforum, 47, 125-137.

Thomas, A., Baptiste, A., Martyr-Koller, R., Pringle, P., & Rhiney, K. (2020). Climate change and small island developing states. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 45(6), 1-6.

World Health Organization. (2018). Climate change and health in small island developing states: a WHO special initiative.

Akiwumi, P. (2022). Climate finance for SIDS is shockingly low: Why this needs to change. UNCTAD