Guest Post by Andreas Wion, 2021-2022 Sustainability Leadership Fellow, and Ph.D. Candidate in the Department of Forest and Rangeland Stewardship and the Graduate Degree Program in Ecology at Colorado State University

When you buy a bag of pine nuts from the grocery store, do you know what’s inside?

Nuts have the highest water footprint of any cultivated crop in the world1. On average, one pound of nuts requires 1197 gallons of water1, which is equivalent to 15 full standard bathtubs. But this varies substantially between varieties of nuts – shelled almonds are nearly double the average water footprint (over 2000 gallons per pound of nuts), while chestnuts are closer to 25% of the average (350 gallons per pound)1. The big difference between these nuts is the amount water used to process and to shell the nuts (accounting roughly half the water footprint of your average pound of nuts), but also the water needed to grow the trees. So are any nuts truly sustainable?

Pine nuts are the edible seeds produced by a small number of pine species across the world. While all pine trees produce seeds, relatively few of them produce nuts – which are simply seeds large, edible seeds. If you’ve never seen a pine nut, they are usually smaller than a peanut, light cream colored with a buttery flavor, and are commonly used in pesto and cookies, ground into flour, topped on a salad, or simply eaten alone as a snack. Almost all pine nuts are wild harvested, and the size and location of harvests vary considerably from year to year and region to region. This is because most conifers are ‘masting’ species, meaning seed production varies synchronously within a population from year to year, and large seed crops (mast years, or bumper crops) may only occur once every 3-7 years. This boom-and-bust dynamic makes balancing supply and demand across years a major challenge, including sourcing labor to harvest and process seeds. Due to the low supply and high demand for pine nuts, they are often the most expensive nut by weight available to consumers in US grocery stores. Yet since 2009, global export demands for pine nuts have risen by more than 50%.2

Here in Colorado, we have our own species of nut producing pines, the piñon pine (Pinus edulis). This tree is found in low elevation, dry woodlands across much of the western slope, and south of Colorado Springs along the Front Range. The northernmost stand of isolated piñon pines in Colorado is just north of Fort Collins, along Highway 287 at Owl Canyon. It’s a short statured tree, rarely reaching more than 10 meters tall, with sweet smelling needles in bunches of two. Piñon pine nuts, also called piñones, are somewhat smaller than your average pine nut, but with a richer, more buttery flavor, and a higher fat content than most other pine nuts. You will rarely see piñon pine nuts on a shelf in a grocery store though. In fact, the bulk of global pine nut production occurs in China, Russia, and Korea – the pine nuts we buy in the store are most often Korean stone pine (Pinus koraiensis). So why are we importing expensive pine nuts from across the globe when we have millions of acres of piñon pine right here at home?

The truth is, there has never been a large commercial pine nut industry in the southwest United States.

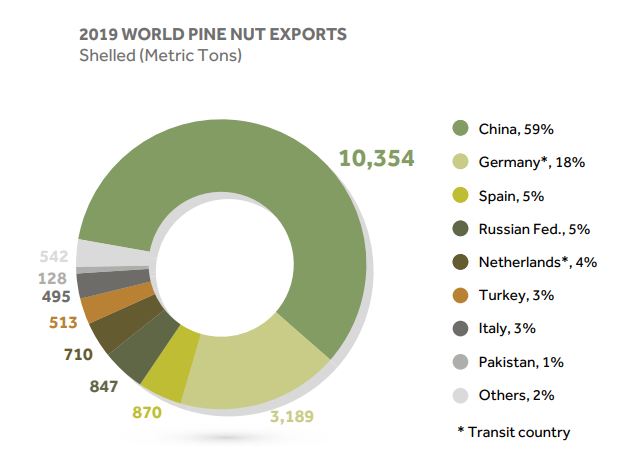

In 2019, China alone accounted for 59% of all pine nut exports globally, and most of these nuts (50%) wind up in store shelves in Europe, the UK, and the United States2. The strong North American and European demand for pine nuts have come at the expense of forest types abroad. For example, intensive nut harvesting of conifer forests has degraded broadleaf forests in some parts of east Asia3. Anecdotal stories of cone collecting camps that establish following bumper crops describe chaotic, sometimes dangerous situations4. Some consumers report experiencing a temporary and minor condition called ‘pine nut mouth’ which is a lingering metallic taste that occurs from ingesting seeds from Pinus armandii, a non-edible species that frequently co-occurs with Pinus koraiensis and is occasionally accidentally harvested. Nevertheless, the global demand (and demand here at home) for pine nuts continues to grow at a rapid pace.

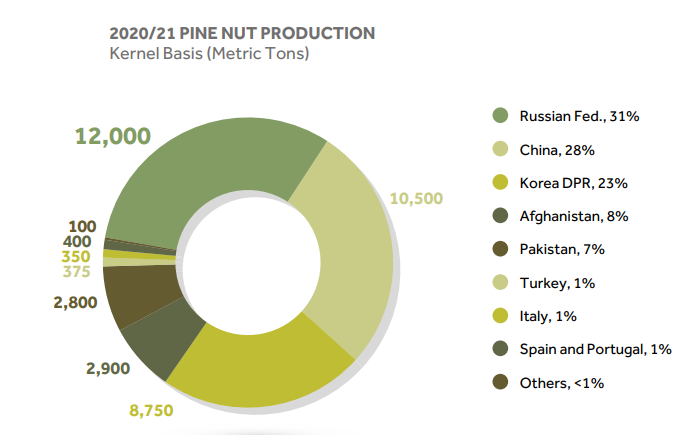

So how sustainable are pine nuts compared to cultivated nuts? First off, pine nuts make up 1% of the world tree nut production by weight in 2020/2021, or 38,175 metric tons2. Therefore, the current environmental impact pine nut harvesting is much more localized relative to the extensive system of cultivated nut orchards across the glove. Because pine nuts are mostly wild gathered, they do not require intensive irrigation like cultivated almonds or pistachios. Nevertheless, most of the sustainability issues surrounding pine nuts come from carbon costs of shipping of pine nuts across the globe. Locally sourced, unshelled pine nuts may present a sustainable alternative to purchasing imported pine nuts.

Good pine nuts are a matter of a piñon

Piñon pine nuts have been identified as a potentially important source of native foods in many areas of the southwestern US5. Fostering markets for native plants could increase food resiliency and security in rural areas. But balancing the costs of labor and production across bumper years and crop failures is a challenge for small, local producers. Forecasts of seed production may help foster local pine nut markets in the southwest5.

Much of the research for my dissertation was focused on understanding the drivers of variable seed production in dry pine species of the southwestern US. Most of my interest in this came from wanting to understand forest regeneration following fires and droughts, but I began to realize this work had implications for pine nuts as well. In piñon pine, large seed crops are associated with cool temperatures and wet weather during the two-year period before seeds mature. Cool, wet autumns followed by cool, wet springs are often associated with large seed crops, two years later. Cones are initiated in the autumn and pollinated the following spring, and the joint success of these two independent events can determine the spatial extent of crops across a landscape. In addition, we found that cooler and wetter areas (for example, higher elevations) produced more cones, more often than hotter and drier areas6. This information helps us understand the spatial variability in cone production across the landscape, and which areas are likely to be producing the most cones in any given year. This information can also be used to develop forecast maps of piñon pine seed crops, which can tell us when and were we are likely to find pine nuts and may help foster local pine nut markets in rural communities. The potential for piñon pine forests to foster food security and sustainability into the 21st century remains largely untapped.

DIY pine nut harvesting

If you want to decouple yourself from the global pine nut supply chain, you can choose to harvest your own pine nuts. If you do choose to harvest your own pine nuts, here’s some tips for doing things sustainably, as well as some important guidelines to keep in mind.

Humans have been gathering, processing, and eating pine nuts for thousands of years. These continue to be important cultural practices to the many tribal communities living across the western US. Respecting, maintaining, and preserving these traditions should always be paramount for land managers who are regulating public access to cone collecting, and should be front of mind of any individual who chooses to participate in the long human history of gathering pine nuts.

It is important to follow all rules and regulations of the land you are collecting on. Collecting in National Parks is never allowed, but the Bureau of Land Management and the Forest Service has a simple permitting process for any potential collectors. Contact your local land management office for more information.

- Never use a pair of shears or loppers to cut off whole branches, or even the tips of branches. This damages the tree and alters the tree’s ability to continue producing cones on those branches. It’s recommended you use a long stick with a hook to knock cones from branches, or to gather cones that have already fallen. Some people lay a blanket beneath the tree and shake the branches, catching the cones that are easily released.

- Never take all of the cones from a single tree, and never take more than you need. Pine nuts are an important food source for birds and mammals.

- Look for stands at higher elevations for your best chance of finding pine nuts in any given year. But even better, pay attention to your local surroundings, the fall and spring weather, and look for evidence of developing (growing) cones.

- Cones that are green in early summer will develop into fully sized mature cones by Labor Day weekend. Cones may open earlier in a dry year. Pulling green cones too early will result in underdeveloped seeds, and if you’re too late, birds and other animals will likely gather the bulk of the seeds. While you’re out, don’t forget to look for chokecherries, which make a nice syrup and ripen around the same time as pine nuts.

- Store cones in paper bags, cardboard boxes, or burlap sacks. They will be dripping with sap, so wear gloves and clothes you don’t mind ruining. Isopropyl alcohol works well for getting sap off your hands. Spread cones out in a dry place like a garage or a basement. They should open in a few days or more, depending on the moisture content. You can speed this process up with a drying oven.

- Shake the seeds loose from the cones. Filled seeds are a dark brown color, and unfilled seeds are a lighter tan color. Birds can distinguish between these and will often take the darker seeds while leaving lighter colored seeds in a cone. Also look out for seeds with insect damage. These will have small holes in them and will be filled with frass. Don’t eat them.

- If you prefer, you can roast the seeds, shelled, in the oven. Some say high temperatures for a short period (450 for 10 minutes), others do low temperatures low long periods (250 for an hour). Just keep an eye on them. When they smell fragrant, like toast and butter, take them out of the oven and let them cool. Don’t let them burn.

- There are many ways to shell the nuts. You can use your teeth, or gently crush them between a towel and a moderate sized book. Experiment with different approaches until you find what works best. Store nuts in a dry container, they’ll keep for some time. Shelled seeds will spoil sooner. They’re best hot and freshy roasted.

For more information, I recommend the book “The piñon pine: A natural and cultural history” by Ronald M. Lanner7. It comes with a section on pine nut cooker by Harriette Lanner.

Citations

1) Mekonnen, M. M., and A. Y. Hoekstra. 2011. “The Green, Blue and Grey Water Footprint of Crops and Derived Crop Products.” Hydrology and Earth System Sciences 15 (5): 1577–1600. https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-15-1577-2011.

2) International Nuts and Dried Fruits Congress. Statistical Yearbook 2020/2021. https://www.nutfruit.org/industry/technical-resources?category=statistical-yearbooks

3) Zhao, Fuqiang, Hongshi He, Limin Dai, and Jian Yang. 2014. “Effects of Human Disturbances on Korean Pine Coverage and Age Structure at a Landscape Scale in Northeast China.” Ecological Engineering 71: 375–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2014.07.072.

4) Slaght, J. C. (2015). Making Pesto? Hold the Pine Nuts. New York, NY: The New York Times.

5) Pearse, Ian S., Andreas P. Wion, Angela D. Gonzalez, and Mario B. Pesendorfer. 2021. “Understanding Mast Seeding for Conservation and Land Management.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 376 (1839). https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2020.0383.

6) Wion, Andreas P., Peter J. Weisberg, Ian S. Pearse, and Miranda D. Redmond. 2020. “Aridity Drives Spatiotemporal Patterns of Masting across the Latitudinal Range of a Dryland Conifer.” Ecography 42: 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.04856.

7) Lanner, Ronald M. 1981. The Pinon Pine: A Natural and Cultural History. 1st ed. Reno, Nevada: University of Nevada Press.