Guest Post By Molly Butler, 2019-2020 Sustainability Leadership Fellow and Ph.D. Candidate in the Department of Microbiology, Immunology, and Pathology

Let’s face it. Climate news is depressing. I know this is nothing new, but yikes. Shall we recap? Fires in Australia have threatened the survival of an unknown number of species. 2019 was officially the second hottest year on record. Fires, flooding, hurricanes, tornadoes, bomb cyclones… despite all this, nothing really changes on the policy front and we continue sauntering on with our blinders up. So things are not great, folks.

And yet, I keep thinking about something my microbiology PhD advisor says all the time: “Never underestimate life.” He says this to warn me how easy it is to contaminate the laboratory dishes I use to grow cells in culture. It takes very little for unwanted bacteria from the air, my hands, or other surfaces to make a happy home in my should-be-sterile cell culture dishes. But lately, I’ve been thinking about this “never underestimate life” mantra in the context of our warming planet. While it doesn’t change the reality of the situation, it gives me both motivation and hope that maybe life on this planet isn’t hurtling toward apocalyptic doom and destruction (not to be too dramatic here).

Never underestimate life. Life finds a way.

There is a never-ending supply of incredible feats of biology, of life finding a way in the most ridiculous of circumstances. In the spirit of being a huge biology nerd and needing to find some bright spot in the gloom, here are a few of my favorite examples of capital-L-Life sticking it to the man.

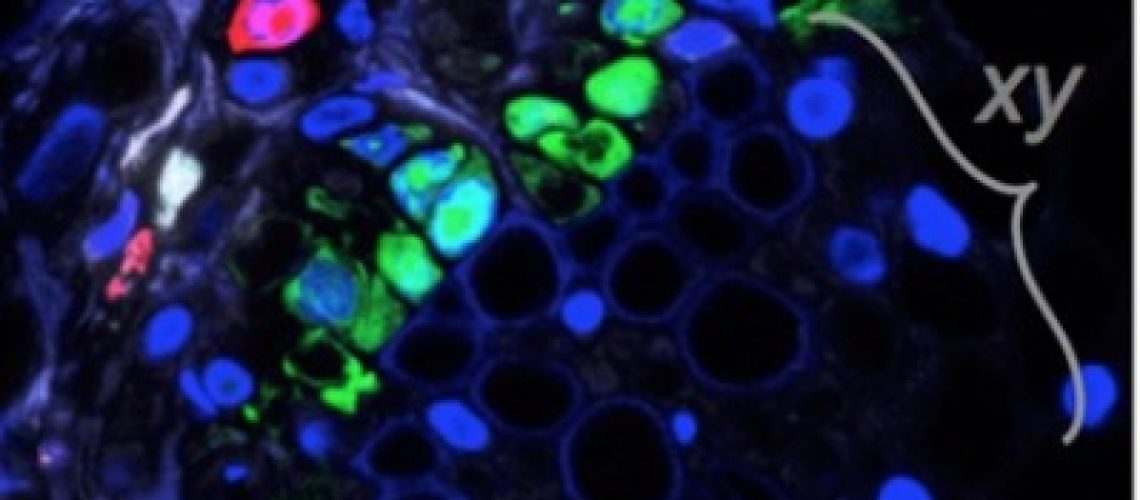

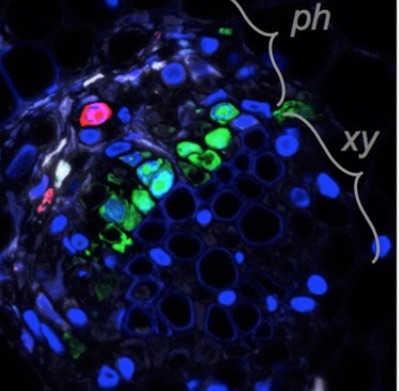

As far as not-following-the-rules goes, viruses are the ultimate rebels. They balk at what scientists call the central dogma of biology – that genetic information is stored as DNA, interpreted through an RNA intermediate, and ultimately expressed as protein. Some viruses follow this, but many, many couldn’t care less about our “central dogma.” But my favorite, most recent example of a virus defying expectations is described in this article from eLIFE. The faba bean necrotic stunt virus (great name, by the way) has no regard for the typical definition of virus. Traditionally, a virus is defined as an obligate intracellular parasite – meaning that a virus depends completely on the cell which it infects in order to replicate. The viral replication process goes something like this: a virus particle infects a single cell, uses that cell’s machinery to make lots of new virus particles, and repeat. But the faba bean necrotic stunt virus bucks this whole idea of a viral replication cycle within a single cell. Faba bean necrotic stunt virus is multipartite – meaning that its genetic material is not contained in one, but rather, eight pieces of DNA. That’s actually not that unusual for viruses. The kicker here is that these separate pieces of DNA can be in multiple cells but ultimately still make one virus particle. That is bananas. A multicellular virus replication cycle? That is not how this works! How? Why? Mind blown.

Speaking of parasites, have you ever heard of a parasitic plant? I hadn’t until I saw this report about Rafflesia, a giant parasitic plant that can weigh more than twenty pounds and smells like rotting meat. I know I am showing my ignorance here, but until I read this, when I thought of parasites, I thought about viruses, tapeworms, and creepy crawlers that sneak in and steal from their host. But a parasitic plant? I had honestly never thought about it. Sure, I knew that invasive species can deprive other plants of water and nutrition, but a parasitic flower actually growing inside another plant until it bursts out in a giant way? Cool, cool. Rafflesia made the news recently because the largest flower ever discovered was found in Indonesia. This particular flower was almost four feet in diameter. A parasitic flower? A GIANT parasitic flower? Looking at pictures of this thing, I think the definition of flower might be getting stretched here a tad. Not sure I’d want a bouquet of these for Valentine’s day, but it is beautiful in its own, weird way.

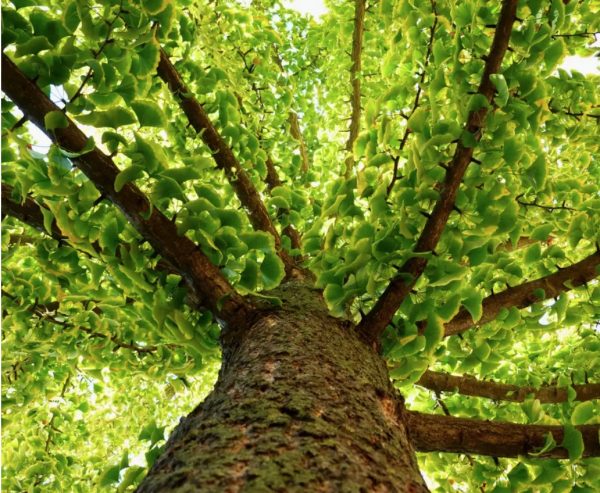

You may not have heard of faba bean necrotic stunt virus, or Rafflesia, but you probably have heard of Ginkgo biloba trees. You might even know that they are ridiculously long-lived. But a recent report in the Proceedings of the Natural Academy of Science gives us some exciting new information on how ginkgo trees manage to live for so long – and by long, I mean thousands of years. In cell biology classes, we learn that normal, healthy cells eventually enter a state called senescence, something akin to old age for cells. This is a central underpinning of aging, that our cells can only divide so many times during our lives and then they eventually run out of gas – gas in this case being telomere length. A cell that doesn’t enter senescence continues to divide, and divide, and divide. This runaway cell division is considered a hallmark of a cancer cell. Right? Wrong! At least in the case of ginkgo trees. They have cells in a specialized area called the vascular cambium which just… don’t enter senescence. They could theoretically live forever barring some kind of outside influence like a natural disaster or an infectious disease. Okay. That’s pretty amazing. I don’t say that in a narcissistic-let’s-steal-from-the-trees-and-live-forever kind of way but in a wow-the-universe-is-amazing-and-I-am-a-tiny-blip-in-time kind of way.

Clearly these examples aren’t even the tiny, tippity-top of the iceberg as far as incredible feats of Life go. I didn’t mention water bears in space, archaea living in extreme environments, or bacterial quorum sensing. There are SO MANY examples of life overcoming absurd obstacles in even more absurd ways. Researching this has been an absolute delight, and I want to know more so tell me about your favorite organism in the comments! And don’t forget to never underestimate life (and also, don’t contaminate your cell cultures, kids).