Guest Post by Olivia Hajek, 2022-2023 Sustainability Leadership Fellow, and Ph.D. Student in the Department of Biology and Graduate Degree Program in Ecology at Colorado State University

In the fall of 2013, Colorado had a very unusual weather event with devastating consequences; record-breaking rainfall totals were observed across much of the Front Range – including the state record for rainfall in a 24-hour period. While Fort Collins saw 5.3 inches of rain, further south in Boulder, totals topped 18 inches in a single week, which amounts to more than its average annual precipitation total.1,2 It wasn’t just the amount of rain that made this event unusual though – when this event occurred further compounded its extremeness. For the most part, large deluges typically occur during the late spring or early summer in this region as part of the monsoon season or with the thunderstorms that can be prevalent during the summer. This event, however, happened during the fall, as a result of a large subtropical airmass essentially becoming trapped over the state.1 With climate change, anomalous events like this are predicted to both become more common and occur at unexpected times.3,4 And since extreme events often have outsized impacts on ecosystems, understanding ecosystem responses to these types of events is critical for forecasting responses and understanding their thresholds and sensitivities.

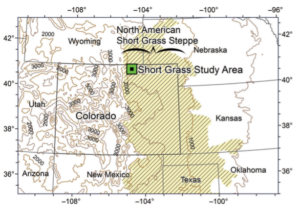

For part of my dissertation research, I decided to use this event to model a field experiment in the shortgrass steppe of Colorado. As the name suggests, the shortgrass steppe ecosystem is dominated by short-statured perennial grasses, and it is primarily used as rangelands. There have been several experiments evaluating this ecosystem’s response to deluges, but all of these experiments have taken place during the summer – when these large events are most likely.5,6 I wanted to understand how this ecosystem responds to such large precipitation amounts in the fall because the impacts are likely different since most of the plants have begun to senesce (ie. leaves have begun to die) and therefore may not be able to utilize the additional soil moisture. In particular, I wanted to see if there were carryover, or legacy, effects observable in the following growing season. Evidence for legacy effects from fall and winter precipitation is limited in the shortgrass steppe7, however, some studies in Colorado did document enhanced plant production for the 2014 growing season, and they attributed this enhancement to the fall rains2. Thus, I hypothesized that during an extremely wet fall, there would be carryover effects; more specifically, I expected that plant growth in the spring would be higher than expected based on spring rainfall alone. Understanding the potential carryover effects would be beneficial for ranchers and land managers because they need to accurately forecast the amount of forage for cattle grazing in order to make critical decisions.

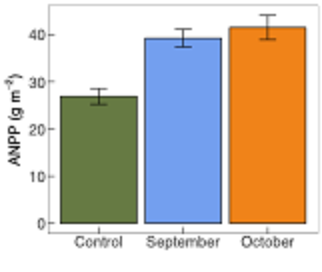

In order to test this hypothesis, I designed an experiment in which I applied 100 mm of water over the course of a week, which corresponded to roughly the same amount of water that this grassland received in September 2013, to twenty m2 plots. I did this precipitation manipulation to ten plots in September and a separate ten plots in October, such that I had three treatments with ten replicates – September deluge, October deluge, and a control, which received no precipitation manipulations. Throughout the fall and through the following June, I monitored these plots, taking regular measurements of ecosystem function. Then, at the end of June, I harvested all of the plant biomass within a subsection of each plot. Essentially, I used scissors to clip all of the grasses to ground level, and then I weighed those grasses to understand the total amount of plant growth within the year. This measurement provides valuable information about carbon cycling and forage production for cattle grazing.

Somewhat surprisingly, I did find evidence for fall carryover effects; plots that received the additional precipitation in September and October showed greater levels of plant growth in the spring. It was surprising because most of my measurements provided little indication that there were spring differences between the treatments – except for soil moisture. Soil moisture levels were higher in the September and October deluge treatments through mid-May, meaning that there was more water available for plant use in the plots that had the fall deluges. This additional water may have been particularly important because the spring of 2022 was exceptionally dry. Late spring into early summer is typically the wettest period for this ecosystem, but this was an extreme spring. Thus, this carryover effect may have only been apparent because of the lack of springtime precipitation.

With climate change, extreme years, seasons, and events are going to become more common. And the impacts of these extreme events are not confined to when the events are actively occurring. Understanding the legacy effects from extreme events is critical for forecasting ecosystem responses and conserving the functioning of these ecosystems. Thus, as scientist continue to study climate extremes, it is imperative that the temporal scale of study corresponds to the period of impact, noting that it may be seasons, years, or even longer after the event has ended.

References:

1Blumhart, M. (2022, Sept. 9). Colorado’s devastating 2013 flood: A look back 9 years later. Fort Collins Coloradoan. https://www.coloradoan.com/story/news/2022/09/09/colorado-2013-flood-anniversary-look-back-estes-park-devastation/67929925007/

2Concilio, A. L., Prevéy, J. S., Omasta, P., O’Connor, J., Nippert, J. B., & Seastedt, T. R. (2015). Response of a mixed grass prairie to an extreme precipitation event. Ecosphere, 6(10), 1-12.

3Donat, M. G., Lowry, A. L., Alexander, L. V., O’Gorman, P. A., & Maher, N. (2016). More extreme precipitation in the world’s dry and wet regions. Nature Climate Change, 6(5), 508-513.

4Hajek, O. L., & Knapp, A. K. (2022). Shifting seasonal patterns of water availability: ecosystem responses to an unappreciated dimension of climate change. New Phytologist, 233(1), 119-125.

5Post, A. K., & Knapp, A. K. (2021). How big is big enough? Surprising responses of a semiarid grassland to increasing deluge size. Global Change Biology, 27(6), 1157-1169.

6Post, A. K., & Knapp, A. K. (2020). The importance of extreme rainfall events and their timing in a semi‐arid grassland. Journal of Ecology, 108(6), 2431-2443.

7Hoover, D. L., Lauenroth, W. K., Milchunas, D. G., Porensky, L. M., Augustine, D. J., & Derner, J. D. (2021). Sensitivity of productivity to precipitation amount and pattern varies by topographic position in a semiarid grassland. Ecosphere, 12(2), e03376.

8Hermance, J. F., Augustine, D. J., & Derner, J. D. (2015). Quantifying characteristic growth dynamics in a semi-arid grassland ecosystem by predicting short-term NDVI phenology from daily rainfall: a simple four parameter coupled-reservoir model. International Journal of Remote Sensing, 36(22), 5637-5663.