By Courtney L. Larson, 2018-2019 Sustainability Leadership Fellow and Ph.D. Student in the Department of Fish, Wildlife, and Conservation Biology

In 2016 Rocky Mountain National Park recorded its highest ever visitor count, 4.5 million people. So did Zion (4.3 million), Yosemite (5 million), and Grand Canyon (5.7 million). People and cars fill parking lots, clog roads and trails, and detract from the sense of solitude and wildness that many visitors seek. The crowding can be irritating, especially when you’re circling the parking lot looking for an open spot. But what most people don’t realize is that visitors can also harm the wildlife that call the parks home.

Researchers from around the globe, including in my lab at Colorado State University, have discovered that seemingly benign activities like hiking, mountain biking, and camping changes how animals use their habitat, raises their stress levels, and can even cause populations to decline. For many wildlife species, public parks and preserves are the best remaining habitat in a landscape highly modified by humans for agriculture, transportation, resource extraction, and housing. Widespread outdoor recreation within parks coupled with extensive development outside their boundaries may make our parks less of a sanctuary than we believe them to be.

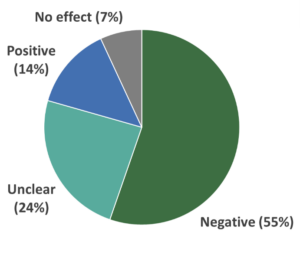

So how exactly can non-motorized, non-consumptive recreation harm wildlife? My research group recently reviewed all the examples we could find in the scientific literature and found that 93% of the studies that assessed the effects of recreation on wildlife found at least one significant effect, most of which were negative. Simply walking a trail doesn’t seem like it could possibly have much of an impact, but when dozens, hundreds, or even thousands of hikers walk the same trail each day, the effects add up. Animals often flee from people or stop what they’re doing to keep a watchful eye on them. If people walk by frequently, it can mean less time for foraging, making it harder to replenish the energy they spend running away. For example, caribou spend roughly half as much time eating when groups of ecotourists on skis were present compared to when they were absent. Wolves near Jasper, Alberta avoid areas near trails, especially high-use trails. When a park is crisscrossed with many miles of trails, animals that avoid trails have a lot less habitat available to use. Recreation can affect reproduction; golden eagle pairs are less likely to lay eggs when there are pedestrians in their territory during the early breeding season, according to researchers from Boise State University. These kinds of effects can have serious consequences for animal populations. Wood turtle populations in Connecticut declined 87% in nine years after the area was opened to hiking and fishing, after holding steady or increasing for the previous nine years without recreation.

Outdoor recreation, just like logging or grazing, is a type of land use. But unlike logging or grazing, recreation does not leave much of a visible mark on the land (most of the time) and is not easily separated from areas set aside for wildlife conservation. There is a widespread assumption that recreation and conservation are compatible land uses. This assumption shows up everywhere from the National Park Service’s mission statement (“To conserve the scenery… and the wildlife therein and to provide for the enjoyment of the same”), to Colorado governor-elect Jared Polis’s stance on public land and the outdoors, to ballot measures such as Larimer County’s 2014 Help Preserve Open Spaces sales tax, which funds open space, natural areas, wildlife habitat, and parks and trails.

So, what can we do? Outdoor recreation is not going away, and we wouldn’t want it to. If, like me, you enjoy getting outside and hiking, camping, or skiing, I’m not trying to make you feel guilty. There are actions that individuals can take to reduce their impact – stay on trail, keep noise levels down, leash your dog, don’t approach wildlife – but the biggest changes need to be made in the way that we plan and manage natural areas. Many wildlife species need at least some space with minimal human intrusion. Cities, counties, states, and the federal government own and manage large systems of parks and preserves; with coordination among these agencies, we could have a well-planned network of preserves with areas that are open and closed to recreation across various habitat types. Within parks, trails can be concentrated into one portion of the park’s area while the rest remains trail-free. In parks with existing trails, this might mean closing and re-vegetating a few of the more far-flung trails. Collaboration with outdoor recreation groups (e.g., mountain biking associations) could help ensure that the best areas to hike and bike remain open.

Of course, we don’t have all the answers. Researchers, myself included, are still working on identifying which species are the most sensitive and how we can minimize the negative impacts of recreation. In the meantime, we need to take precautions to protect wildlife. We can re-open trails, but it’s much harder to bring back wildlife populations once they’re gone.