Guest Post by Ellie Ellis, Ph.D. Candidate in the Department of Soil and Crop Sciences and Trainee in the CSU InTERFEWS Program

Carbon isn’t bad.

Before I make such a controversial claim, let’s get some facts straight…

- There is far too much carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

- The increasing concentration of these gases is undoubtedly due to human activities, including the combustion of fossil fuels, industrial processes, deforestation, and destructive agricultural practices.

- Carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases are already causing severe climate change, and the worst is yet to come. Our failure to respond quickly and seriously to the threat of climate change is sending us towards a future of nearly inevitable 1.5°C global average temperature increase.

The climate solution is dire, but carbon is not the enemy. The true problem is the current imbalance in Earth’s carbon cycle, generated by our actions. We have depleted carbon in critical reservoirs and released it into others. To prevent catastrophic warming and irreversible global changes, we should move towards understanding our influence on the carbon cycle. Most importantly, we should harness this influence to reverse the damage we’ve done.

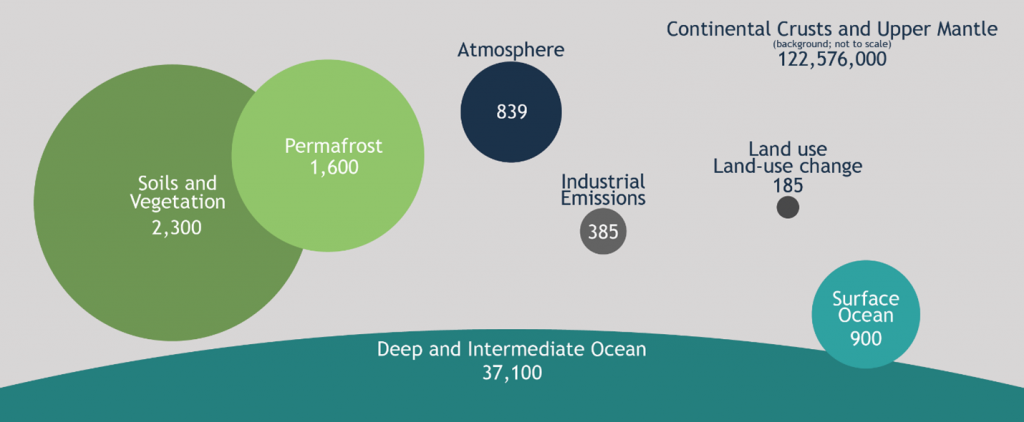

On timescales from minutes to millennia, carbon cycles through Earth’s many carbon pools, including sedimentary rocks, plants, soils, oceans, and the atmosphere. This cycle takes place as carbon is moved from pool to pool, transforming from one form into another. In the geologic system, CO2 is released from carbonate rocks through chemical weathering. In the oceans, CO2 is absorbed or emitted to remain in equilibrium with carbon concentrations in the atmosphere. In the plant system, carbon is absorbed from the atmosphere and transformed into sugars through photosynthesis. In the soil system, carbon contained in plant debris is metabolized by soil organisms, which is either released as CO2 or stored as soil organic matter.

The transformation of carbon is the lifeblood of life on Earth. Countless reactions and interactions take place between organisms and their environments to keep carbon on the move. Without these continuous transformations, life on Earth would cease to exist.

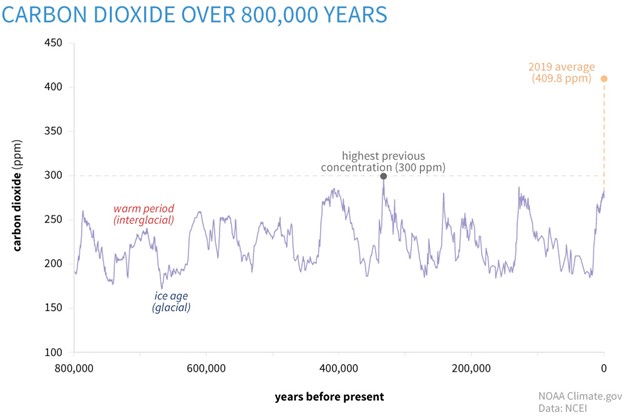

The carbon cycle also regulates global temperatures. Excesses of carbon dioxide (and other greenhouse gases) in the atmosphere result in warmer temperatures, as heat from the sun is trapped by these gases in the lower atmosphere. When left undisturbed, the carbon cycle maintains global temperatures at an equilibrium by balancing the amount of carbon in the atmosphere and other reservoirs.

On the scale of centuries to decades, humans have accelerated the release of carbon from several reservoirs, bending the carbon cycle to meet the demands of modern society. We liberate nearly 37 billion tons of carbon (in the form of CO2) per year from fossil fuel reservoirs to power everyday life. We also exert influence on carbon stored in plants and soils, releasing over 9 billion tons of carbon into the atmosphere per year through land use changes such as deforestation, grassland conversion, and agricultural intensification. We continue to deplete terrestrial (land-based) carbon pools while adding to the atmospheric pool, pushing the carbon cycle further and further into disequilibrium. Worse still, the skyrocketing concentration of carbon in the atmosphere is initiating global changes at a rate unparalleled by any period in the last 800,000 years.

Even if we were to halt emissions tomorrow, we have already released enough greenhouse gases into the atmosphere for climate change to proceed and worsen considerably. To stand a chance of averting some of the worst effects of human-induced climate change, we need to replenish some of the terrestrial carbon stocks we have depleted. To do this, we must target the elements of the carbon system that can respond to influence on human relevant scales and timelines.

Let’s focus on an activity that receives plenty of negative press for its impact on the climate: agriculture. The impacts of agriculture on the environment reach far beyond methane belching cows and nutrient-loaded rivers. Many agricultural practices, including tillage, overuse of agrichemicals, and monoculture cropping, release carbon from the soil much quicker than it can be replenished through natural processes. A recent study estimates that 12,000 years of agricultural land use have released 147 billion tons of carbon from the soil, with the most significant losses occurring from 1800 to 1900 as deforestation and tillage of fertile lands accelerated across the globe.

As soil mismanagement has released stored carbon into the atmosphere, it has also depleted essential soil fertility upon which we depend. Luckily, we now understand what agricultural practices deplete carbon from the soil and what practices replenish what has been lost. Replenishing soil organic carbon stocks relies on the proper management of soil organic matter: the living and dead plant and animal tissues that comprise a small (but absolutely essential) fraction of the soil. In addition to storing carbon, soil organic matter is essential to the health of organisms and plants that call the soil home. Soil organic matter acts as a “bank” of carbon and nitrogen, two essential elements involved in all biological processes that occur in the soil. This soil organic matter bank undergoes frequent investments and withdrawals as plants and soil organisms use carbon and nitrogen to grow and reproduce. Soil organisms of various sizes, including earthworms, nematodes, and microorganisms (such as bacteria and fungi), breakdown soil organic matter to fuel their metabolisms and release nutrients into the soil for plants to use. As plants and soil organisms die, they become a part of the soil organic matter fraction.

A consequence of the breakdown of soil organic matter is the release of volatile CO2 into the atmosphere. Without continuous soil organic matter investments, the stocks will be depleted by soil organisms, and plants will not have access to the nutrients they need. Additionally, without sufficient organic matter soils struggle to retain moisture, regulate pH, and are more susceptible to erosion.

Any activity that influences the activity of microorganisms in the soil will impact the stock of soil organic matter. For example, replacement of diverse ecosystems with a single crop influences the diversity of organisms lying underground because different plant species excrete unique substances from their roots that support specific microorganisms. Without plant diversity above ground, communities of organisms below ground become less varied. This decrease in diversity may lead to an outbreak of pathogenic organisms and soil disease. In fact, recent research suggests the diversity of species and functions above and below ground may be the key to locking more carbon in the soil carbon reservoir. Additionally, conventional tillage practices breakdown soil aggregates, which are the clumps of soil made up of silt and clay mineral particles that bind organic matter and provide a favorable structure and microenvironments for plant roots and microorganisms to thrive. Activities like tillage that disrupt the soil structure, often lead to compaction and accelerated erosion, washing away topsoil where essential organic matter is stored.

But not all hope is lost. Just as improper management can release soil carbon, best management practices can replenish soil carbon reserves. If we want to increase the wealth of our soil carbon bank, it must be managed in a way that promotes consistent organic matter investments and reduces volatile withdrawals from the account. Using a suite of regenerative practices, farmers can harness the power of photosynthesis to build soil carbon reserves and manage the forces of decomposition. For example, farmers can plant diverse mixes of crops over several years that bolster microbial activity in different ways. A common crop rotation in non-irrigated croplands in Colorado is wheat-corn-millet rotation which has replaced some areas previously cropped to a monoculture of wheat, followed by a fallow year when no crops are planted and the soil is left bare. Diversified crop rotations have replaced some areas previously cropped to a monoculture of wheat. Cover crops are another useful strategy for replenishing soil organic matter because the soil is never laid bare and organic matter is continuously added to the soil. Leguminous plants such as peas, alfalfa, or vetch are popular cover crops because they host bacteria that “fix” nitrogen from the air and render it available to plant roots. Additionally, minimizing or reducing tillage maintains soil structure and protects organic matter from accelerated decomposition. No-till practices also increase the water holding capacity of soil, increasing farm resilience to drought and floods. Investing in the soil carbon bank is a win-win solution: rebuilding soil organic matter will reduce agricultural greenhouse gas emissions, improve soil fertility, and prepare soils for the climates of the future.

When we look back on this critical period in human history, we should feel we pursued every possible avenue of climate change mitigation. But let’s not forget… the need for urgent and dramatic reductions in fossil fuel emissions is paramount. Fossil fuel companies and other major emitters must act now to dramatically decrease and eventually cease our reliance on fossil fuels. In fact, this should have happened 10 years ago. The situation is dire. It’s time to consider solutions that reinvest carbon in depleted reservoirs, and this is where we turn to soil.