Guest Post by Maksim Sergeyev, 2023-2024 Sustainability Leadership Fellow, and Postdoctoral Fellow in the Colorado Natural Heritage Program at Colorado State University

Vermin or vital: The complex case of the prairie dog.

Rolling meadows and countryside are as synonymous with American heartland as apple pie and baseball. These sprawling grasslands are home to a variety of native plant and wildlife species, as well as providing much of the space for agriculture and livestock grazing. As such, maintaining healthy grasslands is essential to our current way of life; however, North American grasslands are among the most threatened ecosystems in the world. Grasslands today are under threat from urban development and land conversion, climatic extremes, and introduced, nonnative species and diseases. Mitigating these threats involves several challenges, including complex land ownership, limited funding, and the large spatial scale at which ecosystem processes are occurring. Many of these challenges are summarized in the case of the prairie dog and their controversial role in North American grasslands.

Prairie dogs…but aren’t those vermin?

While some do indeed consider prairie dogs vermin, their role in grassland ecosystems suggests they are actually more of a necessity than a nuisance. Prairie dogs are a burrowing rodent native to North American grasslands. In the past, grasslands featured expansive colonies of prairie dogs; however, today, prairie dogs exist in smaller, fragmented colonies in only a small subset of their historic range (98%). As prairie dog colonies have declined, so too have the health of grasslands and associated species.

Well why are they so important?

In ecology, prairie dogs are commonly known as a keystone species, meaning they have a dramatically large effect on the ecosystem relative to their abundance. This is due to their connection to other species and ecosystem processes. However, prairie dogs are not only a keystone species, but also an ecosystem engineer, a species which modifies its habitat through its activities. Through their ecosystem engineering activities, prairie dogs create both above and below ground habitat for other species. By eating and clipping above ground vegetation, prairie dogs create open patches of grassland habitat that many species associate with, including ground-nesting grassland birds such as the threatened burrowing owl and mountain plovers. In addition, their burrows create below ground habitat for a variety of arthropods, reptiles, birds and other mammals. If all of that weren’t enough, prairie dogs also act as an important food source for grassland carnivores including foxes, coyotes, badgers, bobcats, several raptor species and the highly endangered black-footed ferret, the most endangered mammal in North America.

If they are so important, why the controversy?

While the many beneficial impacts of prairie dogs have been well documented, conservation of prairie dogs remains a controversial and challenging issue. Today’s grasslands are a complex matrix of public and private land, full of fences and intricate jurisdictional boundaries, complicating conservation efforts. As such, managing prairie dogs requires balancing conservation of native wildlife with the competing interests of livestock producers, who often advocate for smaller colonies of prairie dogs because they can compete with cattle for the grass that they eat, particularly during drought years. Further complicating management, prairie dogs are highly susceptible to sylvatic plague, resulting in high volatility in population size wherein portions of entire colonies may be lost due to plague only to regrow in the following years. This uncertainty in size and location of prairie dog populations complicates management for both ranchers and management agencies.

So, what is the solution?

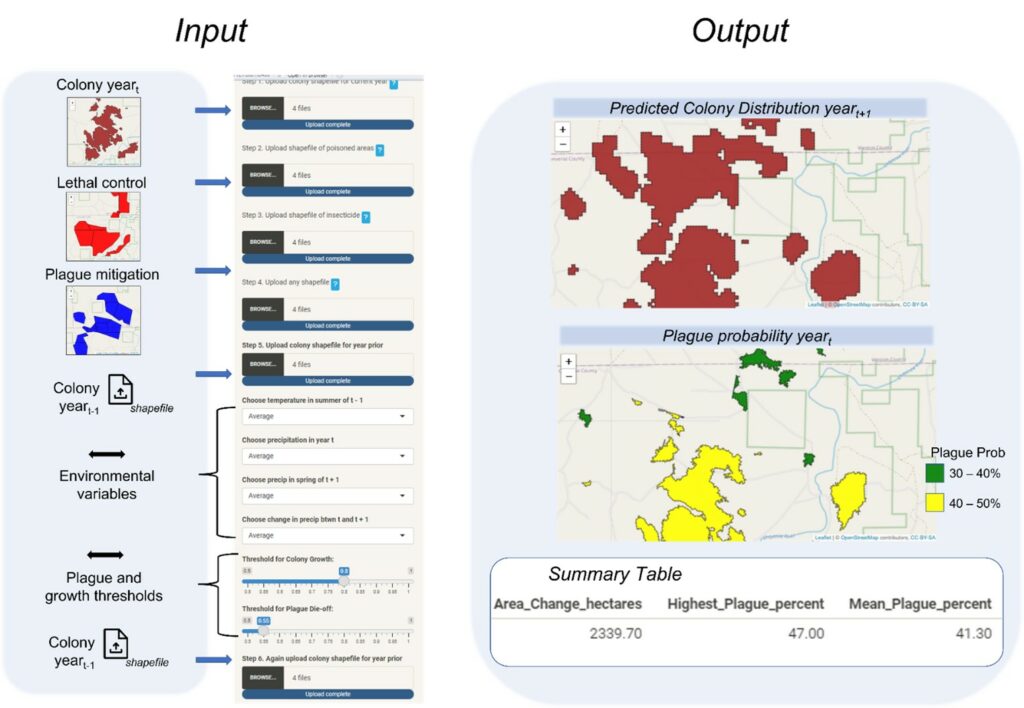

Great question. As is often the case in ecology, the short answer is: it depends. For one thing, management goals and site conditions vary greatly throughout America’s Central Grasslands. For another, funding for management is often limited and must be allocated to manage a variety of species. Managers do have options though, with the ability to either remove prairie dogs from unwanted areas through lethal or nonlethal means, or to protect prairie dogs within an area from plague through vaccines or insecticide to kill the fleas that carry plague, thus increasing the likelihood of large, stable populations. As both management strategies can be costly and labor intensive, it is imperative to apply these strategies only when necessary and in a manner that maximizes their effectiveness. Researchers at CSU, in collaboration with other institutions, recently developed PDOG MAPR, an application that land managers can use to predict changes in prairie dog populations and the likelihood of plague from year to year. Further, managers can input areas that they are considering managing and examine how those proposed actions will impact prairie dogs. This tool can be used to inform conservation of prairie dogs to maximize management actions and achieve desired objectives.

Conclusion

The case of the prairie dog will likely continue to remain a controversial one, as conservationists advocate for larger colonies to support native grassland biodiversity, while livestock producers will likely remain proponents of smaller colonies to better suite their needs for cattle production. What is certain though, is that healthy prairie dog colonies will remain beneficial to the grassland, and what is good for the grassland is good for the cattle and in turn us as consumers. And so, in the case of the prairie dog, vermin or vital, you decide.