Guest Post by Randall Bonnell, 2023-2024 Sustainability Leadership Fellow, and Ph.D. Candidate in the Department of Geosciences at Colorado State University

The mountains and their snowpacks are defining features of Colorado. Here, seasonal snow supplies more than 70% of the annual streamflow and is thus a vital resource for municipal, agricultural, and industrial water supplies.1 Colorado’s economy is intrinsically linked to snow. In the winter, snowpacks support the Colorado ski industry, which constitutes 24% of the GDP generated by skiing across the nation.2 As the snow begins to melt, the rivers rise, and the rafting and fishing industries take over. However, Colorado’s average temperatures have warmed by nearly 2°C since the 1980s, shifting seasonal snowpacks up in elevation, reducing the amount of snow, and initiating earlier snowmelt.3 These changes have increased the uncertainty for future availability of snow water resources, extended and amplified the wildfire season, and decreased the extent and volume of Colorado’s glaciers.

A Lower-Snow Future for Colorado Yields Less Water for its Residents

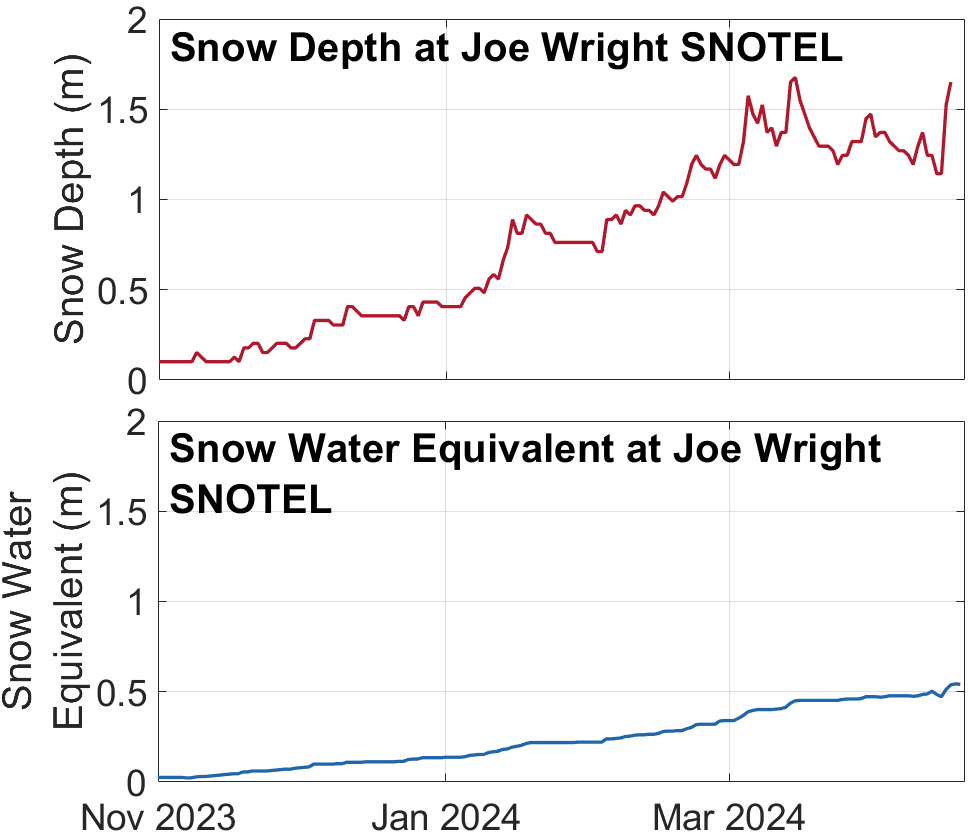

Snow water equivalent is a key term used for describing the amount of water stored in the snowpack, or more specifically, the height of water that would be produced if the entire snowpack melted. Snow water equivalent increases as elevation increases and our seasonal snowpacks commonly accumulate 0.2 to over 1.0 m of snow water equivalent by springtime. The figure below shows an example of snow depth and snow water equivalent measurements from an automated station near Cameron Pass in northern Colorado from this winter. As a result of climate change, nearly every long-term snowpack monitoring site in Colorado has seen a decline in snow water equivalent since the 1950’s, with a few sites having lost nearly 80% of the snowpack.4 Further losses in snow water equivalent and snow covered area, particularly at lower elevations, are expected over the next 50 years.5 These changes are compounded by an earlier start to the snowmelt season, which is initiating 2–3 weeks earlier relative to historical seasons.6 Collectively, a lower snowpack and reduced length of snow season indicate that changes will be necessary for effective water resource management, hence the recent and ongoing negotiations for water rights to the Colorado River.7

A Lower-Snow Future for Colorado Yields Less Water for its Residents

Snow water equivalent is a key term used for describing the amount of water stored in the snowpack, or more specifically, the height of water that would be produced if the entire snowpack melted. Snow water equivalent increases as elevation increases and our seasonal snowpacks commonly accumulate 0.2 to over 1.0 m of snow water equivalent by springtime. The figure below shows an example of snow depth and snow water equivalent measurements from an automated station near Cameron Pass in northern Colorado from this winter. As a result of climate change, nearly every long-term snowpack monitoring site in Colorado has seen a decline in snow water equivalent since the 1950’s, with a few sites having lost nearly 80% of the snowpack.4 Further losses in snow water equivalent and snow covered area, particularly at lower elevations, are expected over the next 50 years.5 These changes are compounded by an earlier start to the snowmelt season, which is initiating 2–3 weeks earlier relative to historical seasons.6 Collectively, a lower snowpack and reduced length of snow season indicate that changes will be necessary for effective water resource management, hence the recent and ongoing negotiations for water rights to the Colorado River.7

The Interplay between Snowpack Reductions and Wildfire Intensification

Beyond water usage, changes to the snowpack have had pronounced effects in both the alpine and subalpine ecosystems of Colorado. In the subalpine, a shorter snow season means a longer wildfire season. Over the last 40 years, wildfires have burned increasingly larger subalpine areas and 2020 saw the largest wildfire season in state history, with the Cameron Peak and East Troublesome wildfires burning more than 1600 km2 of the northern Front Range.8 In the first winter post-Cameron Peak wildfire, burned areas were noted as storing up to 25% less snow than unaffected areas and snow melted out up to two weeks earlier.9 These changes are in part due to char, the blackened debris from burned trees, which lands on the snowpack surface and increases how much solar radiation the snowpack absorbs. Thus, climate change has led to more favorable conditions for wildfires, and wildfires in turn, exacerbate the snow storage and snowmelt timing changes imposed by climate change.

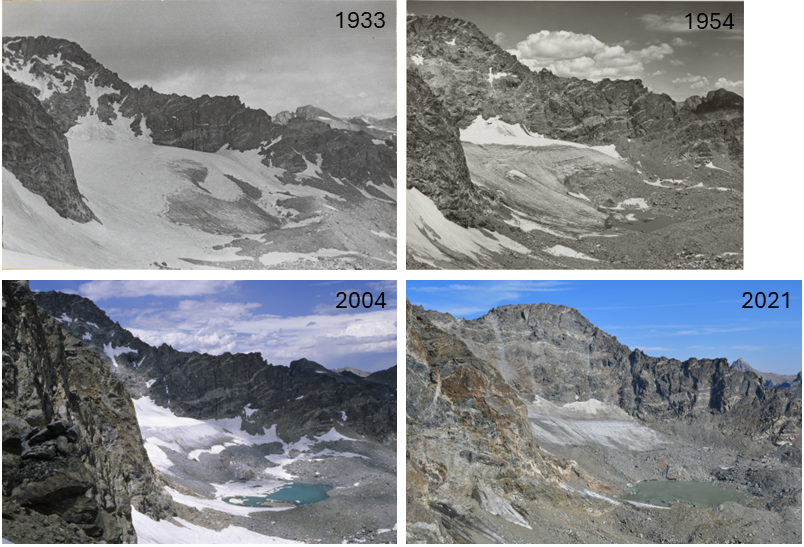

Alpine Reductions in Glaciers and Perennial Snowfields

In Colorado’s alpine regions, warmer temperatures, less snow, and a reduced snow season length have resulted in widespread melting of glaciers and perennial snowfields. Although these ice features are small (less than 0.10 km2), they yield late-season runoff that supports cold-water refuges for macroinvertebrates10 and are popular tourist attractions, such as Andrew’s Glacier in Rocky Mountain National Park. As these features reduce in size, the local topography shades the glacier/snowfield surface from the sun and contributes to the snow supply via avalanching.11 Thus these features have reduced significantly in size, but they may persist longer than expected.

What Can We Do? Opportunities for Involvement

Here, the primary focus has been on the long-term effects of climate change on water resources and on two of Colorado’s most beloved ecosystems. For the curious reader, I recommend researching the many consequences of warming temperatures that are changing Colorado’s environment (e.g., mountain pine beetle infestation, increased frequency of extreme droughts). The changes to the snowpack and the corresponding changes to the environment may feel alarming. Water crisis, glaciers, fires, oh my! But there are ways that you can contribute towards a brighter future. You can make simple adjustments to your everyday life that can go a long way towards reducing your water use and carbon footprint. You could also choose to join a policy advocacy group. Groups such as Protect our Winters12 and The Sierra Club13 advocate for environmental regulations that could help reduce climate impacts from industry. Regardless, it’s late April and there is still plenty of snow in the mountains – I hope you get the opportunity to get out and play.

References

- Li, D., Wrzesien, M. L., Durand, M., Adam, J., & Lettenmaier, D. P. (2017). How much runoff originates as snow in the western United States, and how will that change in the future? Geophysical Research Letters, 44(12), 6163-6172. https://doi.org/10.1002/2017GL073551

- Stiffler, C. (2023). At Odds with the Outdoor Economy: Comparing Colorado’s Outdoor Recreation and Oil & Gas Industries. Colorado Fiscal Institute, 11 pp. https://www.coloradofiscal.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/CFI-Outdoor-Recreation-Report-2023-FINAL.pdf

- Ma, C., Fassnacht, S. R., & Kampf, S. K. (2019). How temperature sensor change affects warming trends and modeling: An evaluation across the state of Colorado. Water Resources Research, 55(11), 9748-9764. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019WR025921

- Mote, P. W., Li, S., Lettenmaier, D. P., Xiao, M., & Engel, R. (2018). Dramatic declines in snowpack in the western US. Npj Climate and Atmospheric Science, 1(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-018-0012-1

- Siirila-Woodburn, E. R., Rhoades, A. M., Hatchett, B. J., Huning, L. S., Szinai, J., Tague, C., … & Kaatz, L. (2021). A low-to-no snow future and its impacts on water resources in the western United States. Nature Reviews Earth & Environment, 2(11), 800-819. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-021-00219-y

- Clow, D. W. (2010). Changes in the timing of snowmelt and streamflow in Colorado: A response to recent warming. Journal of Climate, 23(9), 2293-2306. https://doi.org/10.1175/2009JCLI2951.1

- Hager, H. (2024). As a deadline approaches, Colorado River states are still far apart on water sharing. National Public Radio, [journal article]. https://www.npr.org/2024/03/08/1237056819/as-a-deadline-approaches-colorado-river-states-are-still-far-apart-on-water-shar#:~:text=States%20upstream%20and%20downstream%20of,say%20that%20suggestion%20is%20im

- Kampf, S. K., McGrath, D., Sears, M. G., Fassnacht, S. R., Kiewiet, L., & Hammond, J. C. (2022). Increasing wildfire impacts on snowpack in the western US. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 119(39), e2200333119. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2200333119

- McGrath, D., Zeller, L., Bonnell, R., Reis, W., Kampf, S., Williams, K., … & Rittger, K. (2023). Declines in peak snow water equivalent and elevated snowmelt rates following the 2020 Cameron Peak wildfire in Northern Colorado. Geophysical Research Letters, 50(6), e2022GL101294. https://doi.org/10.1029/2022GL101294

- Brighenti, S., Hotaling, S., Finn, D. S., Fountain, A. G., Hayashi, M., Herbst, D., … & Millar, C. I. (2021). Rock glaciers and related cold rocky landforms: Overlooked climate refugia for mountain biodiversity. Global Change Biology, 27(8), 1504-1517. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.15510

- Mcgrath, D. (2022). Blowing in the Wind: The Glaciers of Colorado. The Mountain Geologist, 59(3), 229–238. https://doi.org/10.31582/rmag.mg.59.3.229

- Protect Our Winters. [website]. https://protectourwinters.org/

- Colorado Sierra Club. [website]. https://coloradosierraclub.org/