Guest Post by Sam Leuthold, 2023-2024 Sustainability Leadership Fellow, and Ph. D. Candidate in the Department of Soil and Crop Sciences and the Graduate Degree Program in Ecology at Colorado State University

Over the course of the last two decades, there has been a shift in the general popularity of agricultural soils. When I was growing up, climate change wouldn’t have qualified as a typical topic of conversation around the dinner table, let alone soil health or the ability of soils to store carbon. It was a topic for farmers or agronomists, outside the sphere of influence for most people. Not so in the modern day, however. Soils are becoming a true kitchen table issue. As climate change has become a more pervasive and urgent political issue, governments around the world have started to look to soil as a potential part of the solution. In the US, politicians no longer limit their discussion of agriculture to the Iowa state fair; stump speeches around the country now highlight investments in regenerative agriculture and soils research. The Inflation Reduction Act, President Joe Biden’s signature piece of legislation passed into law in 2022, allocated $19.5 billion USD to support the USDA’s efforts to mitigate climate change via agricultural soils. These shifts aren’t limited to the public sector either — we have movies streaming on Netflix that employ the dulcet tones of Woody Harrelson to extol the potential for soils to reverse climate change. In an industry once dominated by legacy brands like John Deere, Pioneer, and Cargill, a new generation of companies have come to market, resembling the tech start-ups of Silicon Valley more so than the farmer co-ops of yore. What’s driven this excitement around agricultural soils, you may ask? Why the investment? What’s the catch? All excellent questions, dear reader.

Mechanisms of climate mitigation via soil carbon sequestration

At the root of the excitement around soils is their ability to hold on to carbon, potentially drawing it out of the atmosphere and locking it away. The mechanism for this is relatively straight-forward: when plants are growing through photosynthesis, they’re pulling carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere and incorporating it into plant structures. The amount of drawdown in agricultural lands can be quite dramatic—a 2014 study found that at peak growth, the US Corn Belt (i.e., Iowa, Indiana, Illinois, Missouri, Ohio, and Wisconsin, among other states) was the most photosynthetically active region in the world, the amount of CO2 that was being absorbed outstripping even the Amazon for the short period while growth was at its zenith. After harvest, when the grain is removed and the crop residue and roots are returned to the soil, much of this carbon is returned to the atmosphere as soil microbes use the residue as a food source, respiring CO2 much like you or me. However, due to chemical bonds between soil particles and the organic molecules in the crop residue, as well as the fact that microbes simply might not be able to get to every last piece of litter, a portion of that carbon sticks around, becoming soil organic carbon. In the average agricultural soil, soil organic carbon accounts for just 1-2% of the total soil mass, a rather minuscule amount all things considered. But, when we consider just how much soil there is in the world, we find that soils hold more carbon than all of the plants on Earth, and all of the carbon in the atmosphere, combined. They present a serious sink for atmospheric carbon to be stored.

So why the hype around agricultural soils?

Knowing that soils already hold so much carbon, why do we think that they could serve to store more? The answer to this question is similar to many of the questions that get raised when we start talking about climate change and carbon cycling—humans have fundamentally altered soil carbon dynamics through their activities. Estimates published in the Proceedings of the National Academies of Sciences suggest that over the last 12,000 years, 133 petagrams (i.e., 1.33 x 1014 kg, the emissions equivalent of driving your car for the next 28 trillion years, or roughly three times annual global emissions) of carbon have been lost from soils due to anthropogenic agricultural practices, such as tillage, land conversion, and over grazing. While this is somewhat worrisome on its face (that’s a lot of carbon transferred into the atmosphere!), it also presents a tremendous opportunity. If all of that carbon was lost from agricultural soils, ostensibly we should be able to put at least some of it back, reducing the carbon dioxide concentration of the atmosphere, and potentially mitigating some of the worst effects of human caused climate change.

The upshot here is that we have a decent idea of how we can change agricultural practices to store a little more carbon in the soil. Recent work from Colorado State has shown that practices such as adding a cover crop (a crop grown in between cash crops, and left on the soil rather than harvested), decreasing soil disturbance and the amount of tillage, and even integrating livestock into crop fields tend to increase the amount of carbon in agricultural soils, with the effects increasing the longer the practices are, well, practiced. These are the types of practice changes that underlie the burgeoning soil carbon markets, and represent the sort of actionable steps that the USDA is promoting with their new funding allocation. Of course, mileage may vary, depending on the climate, the soil type, and the specifics of how a given farmer implements their practice, but generally these are the means by which we can use soils as a reservoir for atmospheric carbon

drawdown.

So, what’s the catch?

As previous SOGES fellows have pointed out, rarely if ever do silver bullets exist in agriculture. The system is too interconnected and complex for changes at the farm level to not have ramifications down the pipeline. Of course, there are challenges associated with just measuring carbon changes at the farm scale, and questions around the incentive programs that may foster adoption of carbon sequestering practices, but those have been discussed at length in other venues, and I won’t harp on them here. As someone who thinks a lot about soil carbon, the issue I see as rather under-discussed is what carbon economists call, “leakage.” In this context, leakage can be understood to mean carbon emissions that happen as a result of the implementation of a practice change, but on a different piece of land.

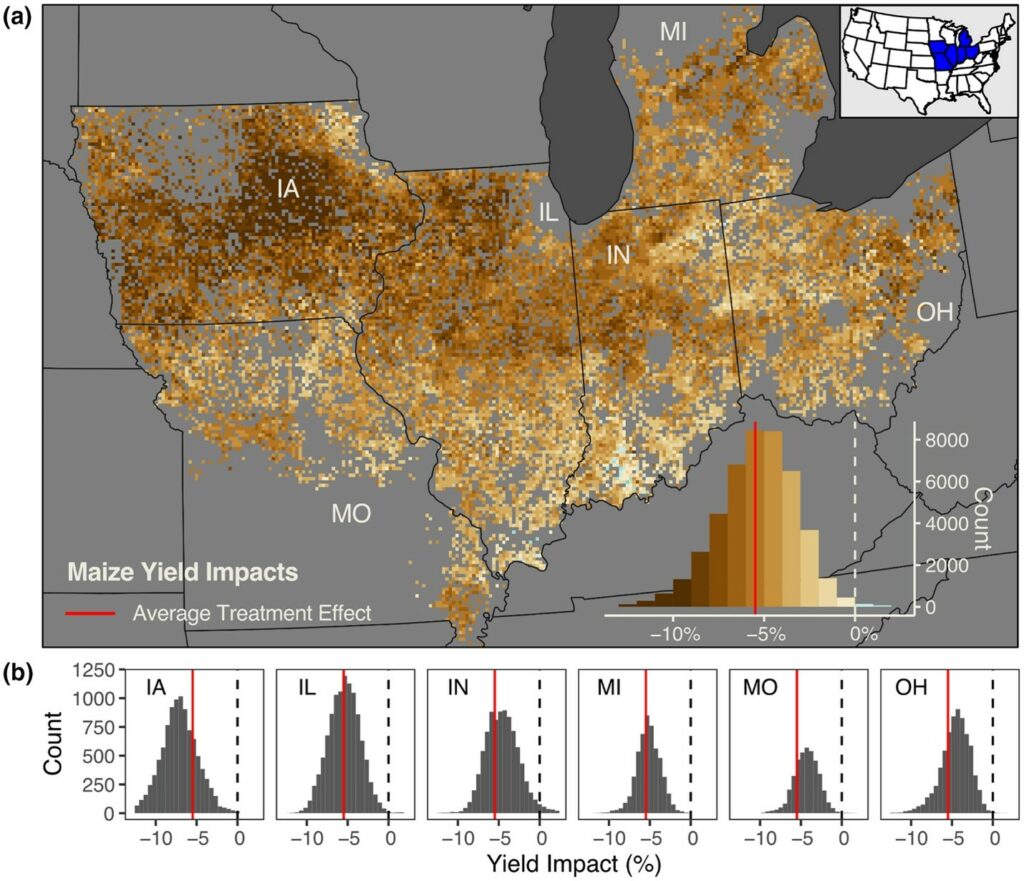

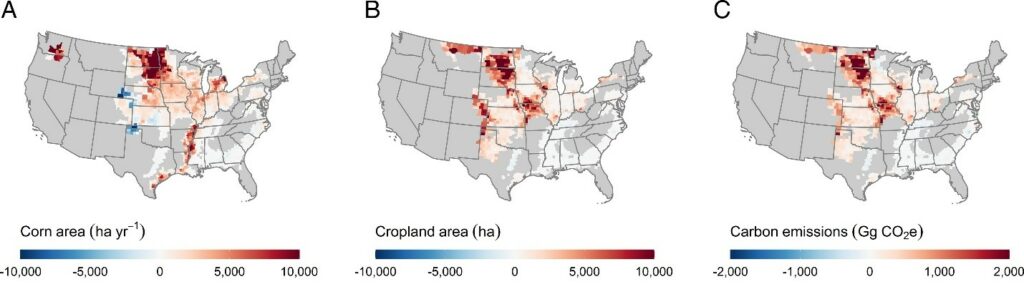

This is important, because while our regenerative practices such as cover cropping and reducing tillage are great for the soil, the jury is still out on their effects on crop yields. A recent study in Global Change Biology looked at 90,000 crop fields across the central United States, using a combination of satellite data and statistical models, and found that cover crop adoption decreased corn and soybean yields by 3-5%. Other work has shown that switching from conventional tillage to no-till agriculture has the potential to reduce yields by up to 5%. These aren’t massive yield losses, but in aggregate, and in a globalized agricultural economy, the loss of even 5% of the US soybean crop is relatively substantial. Importantly, these losses aren’t just cut out of the food system but are often made up for via the expansion of agricultural lands, both domestically and globally. A paper published in Nature Sustainability recently highlighted this issue, demonstrating that when the potential emissions associated with land use conversions due to decreased crop yields are accounted for, the effectiveness of soil carbon sequestration efforts in the United States are decreased by up to 70%. Further, it’s important to understand that this change in land use may not occur in the same area, which can benefit the greenhouse gas budgets of individual countries, while harming carbon reduction efforts globally, often at the cost of sensitive ecosystems.

We’ve seen this issue rear its head before— the 2005 Renewable Fuel Standard was designed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by replacing fossil fuels with fuels made from crop biomass. However, the impact of this increased demand for farm products, mostly corn, led to a significant expansion of agricultural lands, increased fertilizer use, and further environmental degradation. A research group at University of Wisconsin-Madison estimated that the impact of the legislation was at best neutral in regard to carbon emissions, and more likely increased the amount of carbon put into the atmosphere relative to gasoline-based fuels alone due to the conversion of native lands into farmland.

When examined through this lens, the promise of soil carbon seems a little less straightforward than it is initially billed as. However, all is not lost, and leakage is not a reason to despair. It’s simply another thing that we need to keep on the balance sheet as we try to use levers across the agricultural system to decrease and offset emissions. Robust carbon accounting protocols incorporate requirements around leakage (Table A-1 summarizes this nicely), and we can make some predictions about the land use change response globally to altered yields at the national level such that we can account for changes responsibly. Sustainable intensification, the concept of increasing yields on existing farmland while preserving wildlands, offers one route towards maintaining food production without increasing emission intensity via land use conversion, but requires continued research and innovation. The practices that increase soil carbon have demonstrable ecosystem benefits including improved water quality, decreased soil erosion, and providing habitat for pollinators, and are often worthwhile to farmers for these reasons alone.

At the end of the day, we all understand that ecosystems are full of complex interactions, and interfacing ecology with human systems only serves to add another layer of complexity. For agricultural soils to have the biggest impact they can, we need to make sure we’re understanding the full picture the best we can. We need to look beyond the crop field and out to the world at large to truly understand the impact we’re having, and with the right approaches, to maximize it.