Guest Post by Pat Keys, Lead Research Scientist at the School of Global Environmental Sustainability at Colorado State University

Climate change is triggering disasters in the present, and leading to uncertainty about the future. In the Arctic, climate changes are happening faster than anywhere else on the planet. We know stories can transport our minds to think differently about the world, so how can we tell new stories about climate change in the Arctic to understand what the future might hold?

Creating science stories about the Arctic

In recently published work , myself and co-author Alexis Meyer developed a new method for creating stories about the future Arctic. We blend a form of machine learning (called computational text analysis), with systematic story-creation, to produce ten new stories, grounded in the reality of the present but depicting far flung events.

The starting point of our research was collecting more than two thousand news articles from around the Arctic that discuss the future of the region. Next, we let a computer program interpret what these articles were saying about the future, and it gave us sets of words and ideas that seem to appear with one another across these thousands of articles. You might be asking, “Wait, why text analysis?” We wanted to find out whether there were under-discussed aspects of the Arctic future in existing scenario work & that by using public perspectives on the future (i.e. public news articles), we might yield new insights.

The text analysis resulted in 10 coherent and interpretable topics, that we plugged into a creative, structured futuring process, which focused on worldbuilding, character development, and plot design. In other words, we wrote ten short stories about the future Arctic. Our methods included the Mānoa Mashup , SciFi prototyping , and even some approaches from Pixar’s ‘Art of Storytelling’ . We also sought to maximize strangeness, specifically to explore the Possible, Preposterous, and Preferable.

Ultimately, the text analysis led us toward futures that focused on location-specific visions rather than generalized, regional descriptions. This allowed greater depth of detail in the story-based scenarios, including a more fully thought-out world for each possible future.

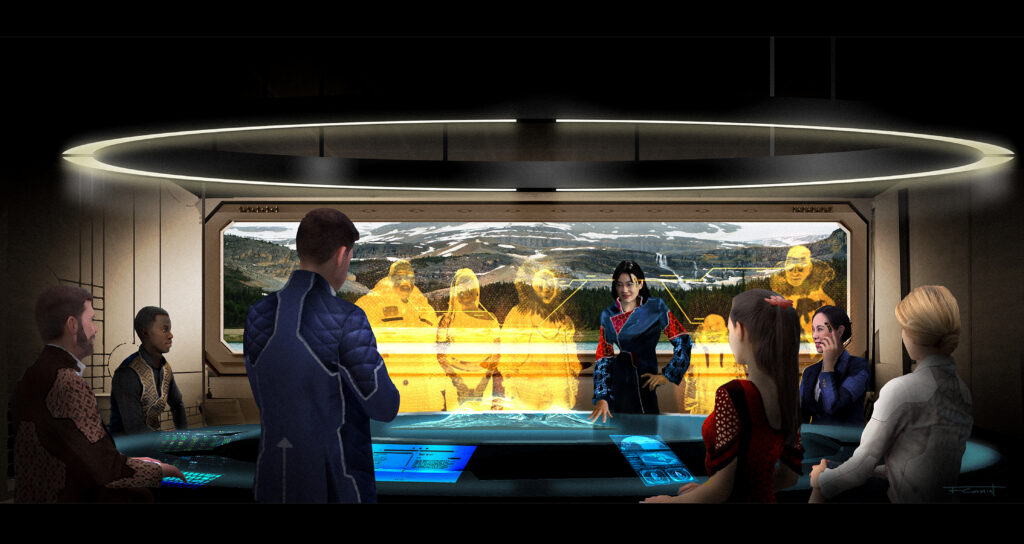

Finally, we worked with a visual artist to design visual impressions of these future Arctic worlds.

A sample of one part of a story about a future conservation effort in Alaska is included here, with its accompanying artwork:

“As the caribou cluster together, we can see the determination in their eyes. These next few days will be the herd’s greatest test.” Gillian intoned, eyes heavy with meaning, as she looked into the camera.

“And, cut! I think we got it that time!” Hank said.

Rachel and Niillas looked at each other, and mimicked Gillian’s tone, “… their greatest test…” then they laughed, stood up, and stretched.

“I know I’m laying it on thick, but the viewers are going to want drama, right?” said Gillian. “And if we don’t add our own drama, this will be .. pretty boring.”

Gillian was, of course, right. As the Porcupine herd was leaving the Gwichʼin Environmental Management Area, and headed into the Prudhoe Coastal Refuge, things were – mostly – very safe. The permafrost bogs could be dangerous given how soft and unpredictable the tundra was. But the caribou were adaptable.

“Think we can make Prudhoe Bay by Sunday?” asked Hank, hopeful at the thought of a warm bed.

“Maybe” said Niillas. ,”The drone monitors show good forage all the way to the coast.” He showed the drone display to the crew, and a 3D map with red veins crisscrossed through a miniature map of the region, with large areas of green.

Rachel pointed to a section of red line split in half, “What happened there? Is that drill road out?” The old oil roads, now serving as refugia for some plants and animals from the surging seas, were also strange, elevated corridors through the swamp. When big chunks of subsurface permafrost melted, the roads would sometimes collapse too, in big gaping sections.

Tell your own science stories.

While we produced ten new story-scenarios for the Arctic, we also provide all the results so that people can join in the creative process. One way to join in is to use the results of the computer-based text analysis. This could be a jumping off point for someone who wants to tell stories about the future Arctic. Second, the story-telling process itself could be used on its own as a blueprint for how to develop your own climate change story.

Empathy engines for just and equitable futures.

Stories can physiologically and psychologically transport us to new places. And while climate change can be a scary, enormous problem — stories might help us navigate this fear with new kinds of hope, and optimistic engagement. Some of the stories in our collection of Arctic scenarios explore a complex texture of fear, hope, danger, and safety. These stories allow us to explore these winding paths of emotion, against a backdrop of a changed planet, and hopefully inspire a realization that many future paths are still possible.

Whether it is writing a story for yourself, your community, or the world — we need more science stories to paint vivid and hopeful visions of the future. Encouraging people to imagine the future and tell their own stories can help them think through the challenges ahead and how they might map their own futures. In the Arctic especially, a place with exceptional cultural diversity, we hope that this work inspires all storytellers to connect more creatively with the future.