Guest Post by Vedanshi Nevatia, 2023-2024 Sustainability Leadership Fellow, and Ph. D. Student in the Department of Economics at Colorado State University

As the urgent need to take tough action towards climate mitigation and sustainability gathers pressure, for most major power-holders today, including the markets, institutions, government agencies, media and countries, environmentalism has perhaps become the biggest fashion fad. “Sounding Green” has not only become politically correct, but also a possible finance-generating mechanism. This is not to say that advertising sustainability by institutions is wrong, but it becomes a problem when looking sustainable pays more than genuinely being sustainable. In other news, the European Parliament decided to ban marketing using greenwashing buzzwords like “environmentally friendly” and “climate neutral” after Apple called its series 9 Apple Watch its first carbon-neutral product!

Climate is a global issue and when complex political systems around the world are brought together, solutions cannot be straightforward. The Sustainable Development Goals outlined by the UN Foundation in 2015 not only provide a guideline for an ideal future, but also illustrate the multi-pronged dilemma of emerging economies. This also means that policies that work for the advanced world might not produce the same results in their counterpart. What is more, these policies might not even work for the former if they aim for a different, greener world. Enough research has shown that Collective Green Action requires the stakeholders to work together, to build technological synergies based on transparency and a public-private partnership that goes beyond borders and profit accumulation. A fundamental requirement then arises for sharing of resources, knowledge and funds that are not tied by the usual risk and return factors that run most of the investment markets. But the problem is that as of today, such instruments or institutions hardly exist.

As per the World Investment Report 2023, much of the growth in international investment in renewable energy, which has nearly tripled since the adoption of the Paris Agreement in 2015, was concentrated in developed countries. Developing countries need renewable energy investments of about US$1.7 trillion annually but attracted foreign direct investment in clean energy worth only US$544 billion in 2022, all of which was exposed to overlapping crises of war in Ukraine, high food and energy prices and debt pressures. What is more, at COP26, advanced economies acknowledged that they have not met their pledges of providing US$100 billion per year in climate finance to developing countries by 2020. The problem here does not lie in the policies being made, but the non-sustainable nature of principles they are based on. If states and companies still rely on risk-based financial instruments and condition-based loans, looking green through high and mighty goals and opaque accountability systems might pay off.

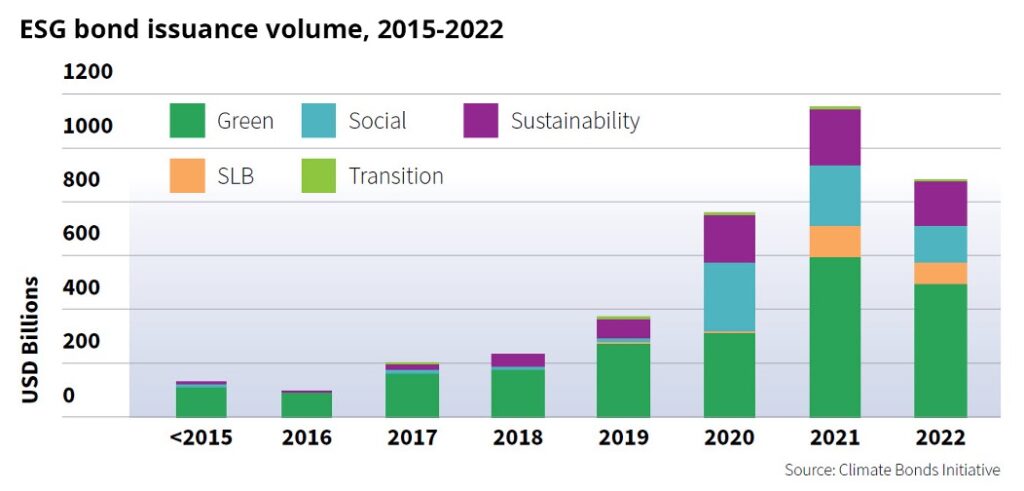

A very good example to understand this trend can be derived from the debate surrounding a comparatively new renewable-project financing instrument termed as Green Bonds. Green bonds are innovative financial instruments specifically earmarked to finance environmentally friendly projects. First issued by the EIB (European Investment Bank) in 2007 in Sweden, green bonds have grown from $11 billion USD in 2013 to $1 Trillion USD in December 2020 globally. They can be issued by governments, financial institutions, non-financial corporations, and the one requirement for them to receive a “green” label is that the use of their proceeds must be for Green, Social or Sustainability purposes. In 2021-2022, when most other kinds of stocks and bonds were experiencing negative growth due to the pandemic, Green Bonds recorded a growth rate of 200%.

A lot of research, although non-conclusive, suggests that the green label on such bonds help in “de-risking” the investment leading to lower cost for the issuer, and they are also in high demand as the investors are anticipating future returns from renewable energy. But without a proper law governing the use of proceeds from Green Bonds, the big question then becomes: is it the altruistic results of green projects, or just the green masking that is leading to such positive trends? The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines greenwashing as “the act or practice of making a product, policy, activity, etc. appear to be more environmentally friendly or less environmentally damaging than it really is.” The Apple-related incident is one mere case which came to light. But with green bonds, the waters of accountability are murkier as there is no straightforward way to check them especially for developing countries which do not have uniform financial systems in place. This also means that for developing countries, even if the green bonds are “less risky”, they are accompanied by the same volatility that their usual investments are. At a time when such countries require green funds not tethered to market conditions (as the problem is not of the market but of the people), they are penalized for market-generated limitations.

My own research on sovereign green bonds spanning 44 countries suggests that the negative premium (lower cost of bonds) appears only slightly significant for the green-labeled ones, but those renewable energy projects which do not have the label, do not enjoy the benefit. Moreover, such bond prices appear to be highly susceptible to oil movements, being more pronounced when demand for fossil fuel is less, for example during the pandemic years. This does not mean that ESG or Green Investing is all bogus, in fact transparent fund-mobilizing for climate mitigation IS the fundamental need of the hour. But it matters how these funds are being mobilized. Transparent country-specific regulations need to be put in place. And more importantly, innovations towards global systems that can mobilize green funds steadily, surely and justifiably need to be designed. As long as green funding is left at the mercy of fashion fad and advertising, it will be self-selecting those that sound convincingly green…and that too till the moment it goes out of fashion, Texas and Florida are just a couple of examples.

Citations:

Ameli, Nadia, et al. “A climate investment trap in developing economies.” (2021).

Karpf, A., Mandel, A. The changing value of the ‘green’ label on the US municipal bond market. Nature Clim Change 8, 161–165 (2018).

Egli, Florian. “Renewable energy investment risk: an investigation of changes over time and the underlying drivers.” Energy Policy 140 (2020): 111428.

Kedward, Katie, Daniela Gabor, and Josh Ryan-Collins. “Aligning finance with the green transition: From a risk-based to an allocative green credit policy regime.” Available at SSRN 4198146 (2022).

Kedward, Katie, Daniela Gabor, and J. Ryan-Collins. “A modern credit guidance regime for the green transition.” The European Money and Finance Forum, SUERF Policy Note Issue. No. 294. 2022.

Zerbib, Olivier David. “The effect of pro-environmental preferences on bond prices: Evidence from green bonds.” Journal of banking & finance 98 (2019): 39-60.