Guest Post by Amanda Cicchino, 2021-2022 Sustainability Leadership Fellow, and Ph.D. Student in the Department of Biology and the Graduate Degree Program in Ecology at Colorado State University

Many of us can remember the first time we used a computer. I was a rambunctious child, so my first memory of a computer is of my older sister typing into our family’s first desktop. Thinking about the computers that I use now, some twenty years later, I can revel at the speed at which technology has developed. I now type into computers of all sorts: cellphones, laptops, and even high-performing super-computers. This pace of technological advancement occurred beyond commercial computers and has contributed to our understanding of the natural world.

Organisms as a Series of Four Letters: ACTG

The four nucleotides (A, C, T, and G) found in DNA are the building blocks of life on earth. Prior to the technological advancements of the past few decades, DNA sequences of organisms were primarily inferred through breeding experiments or molecular techniques (e.g., allozyme gels) that resulted in information about one or a few genes. As DNA sequencing technology advanced and became more accessible (in large part due to the Human Genome Project1) and the computational power to store and analyze these data also increased, so did the opportunity to look within the organisms we study and decipher their genetic code. Now, we can sequence thousands and millions of genes, and even the entire genome (i.e., all the DNA) of organisms!

The four nucleotides (A, C, T, and G) found in DNA are the building blocks of life on earth. Prior to the technological advancements of the past few decades, DNA sequences of organisms were primarily inferred through breeding experiments or molecular techniques (e.g., allozyme gels) that resulted in information about one or a few genes. As DNA sequencing technology advanced and became more accessible (in large part due to the Human Genome Project1) and the computational power to store and analyze these data also increased, so did the opportunity to look within the organisms we study and decipher their genetic code. Now, we can sequence thousands and millions of genes, and even the entire genome (i.e., all the DNA) of organisms!

As researchers began amassing and analyzing this growing amount of genetic data, one result became increasingly clear: genetic diversity within species (i.e., inherited variation among individuals) is important for maintaining biodiversity. Genetic diversity is the foundation for adaptation, and thus is critical for species’ responses to the warming world. Biodiversity cannot exist without genetic diversity. It is alarming that another major result to emerge from this “genomic revolution” is that genetic diversity is disappearing2. For example, habitat loss and fragmentation are isolating organisms from one another, preventing them from breeding and mixing their genes. This isolation can not only cause a decrease in the number of individuals in that species, but also in the variation of genetic information. Overexploitation of wildlife, the emergence of diseases, and dynamic environmental changes can all also lead to decreases in genetic diversity. Integrating the maintenance of genetic diversity into conservation practices is therefore critical to sustaining biodiversity over time3,4.

Reducing organisms to a series of four letters, their genetic code, can help us answer many questions about the present and the past. However, there are limitations to what the genetic code of organisms can tell us. One of those limitations is that genetic variation interacts with the environment and may change every generation. Therefore, making predictions into the future is more challenging and requires combining genetic data with environmental and demographic (e.g., growth rates, age classes) data. Here is where computational power is further harnessed to understand the natural world.

Computer Simulations: Organisms as Letters onto Landscapes as Numbers

First and foremost: Simulations are not a crystal ball. They cannot tell us exactly what will happen in the future. However, they help us make predictions about relative scenarios given the information we have. Dr. Erin Landguth, an Associate Professor at the University of Montana, is at the forefront of the field of integrative landscape genetic simulations. Dr. Landguth and her team of collaborators have developed programs that integrate genetic information with landscape features, demographic data, and dynamic environments (e.g., CDPOP5, CDFISH6, CDMetaPOP7). Researchers can use these programs to predict changes in biodiversity over time given certain scenarios.

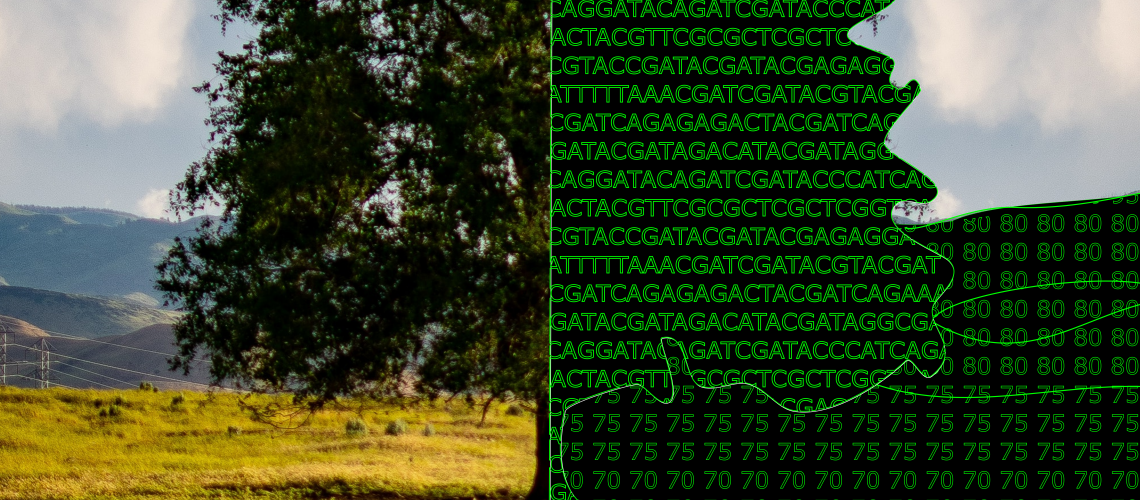

These programs broadly work by reducing organisms to their genetic code and placing them on encoded “landscapes”. Imagine working with a frog species and trying to determine how a frog can move across a landscape that is partly forested and partly open. You can imagine that a frog may move more easily across the forested area than the open area as frogs need to stay cool and moist to survive. Similar logic and formal analyses are used to encode the landscape in question into a matrix of numbers representing the cost of movement across a distance (like on the photo at the top). Then, for each individual, a series of equations are used to encode its demographic data, such as how quickly it will grow, how far from its natal grounds it will move, and how many offspring it will have. These demographic data are then linked to the corresponding genetic data. Now, the organisms are represented by their genetic sequence and have a series of numbers representing their demographic data, and can move on the numerical landscape. The program then simulates organism-environment interactions through time under different scenarios and provides an output of genetic and demographic data.

These programs are powerful tools for predicting how future changes will shape biodiversity. For example, one research group used simulations to investigate the persistence or extinction of tigers in Central India given different changes in land-use8. The authors, led by Dr. Prachi Thatte (currently at the World Wide Fund for Nature – India), simulated tigers on the landscape under different scenarios of land-use change and were able to identify the proposed changes that could lead to the highest number of local extinctions of tigers8. Similar simulation approaches have been used to identify the potential impacts of dam removal on fish movement and connectivity7, evaluate invasive species mitigation options9, and plan for strategic planting of disease-resistant trees10. As Dr. Landguth and her team continue to develop these programs, the ability to predict the outcomes of increasingly complex scenarios is becoming a reality.

These programs are powerful tools for predicting how future changes will shape biodiversity. For example, one research group used simulations to investigate the persistence or extinction of tigers in Central India given different changes in land-use8. The authors, led by Dr. Prachi Thatte (currently at the World Wide Fund for Nature – India), simulated tigers on the landscape under different scenarios of land-use change and were able to identify the proposed changes that could lead to the highest number of local extinctions of tigers8. Similar simulation approaches have been used to identify the potential impacts of dam removal on fish movement and connectivity7, evaluate invasive species mitigation options9, and plan for strategic planting of disease-resistant trees10. As Dr. Landguth and her team continue to develop these programs, the ability to predict the outcomes of increasingly complex scenarios is becoming a reality.

Conclusion

The power of technology has increased our ability to understand the natural world and has given us tools to work to sustain it. By interpreting landscapes as a matrix of numbers and organisms as a series of letters, we can use advanced computational methods like simulations to guide our actions and sustain biodiversity. Perhaps the next time you find yourself in nature, ask yourself: What would it look like if the matrix changed?

References

- Schloss, J. A., Gibbs, R. A., Makhijani, V. B., and Marziali, A. (2020). Cultivating DNA Sequencing Technology after the Human Genome Project. Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics 21:117–138.

- Leigh, D. M., Hendry, A. P., Vázquez-Domínguez, E., and Friesen, V. L. (2019). Estimated six per cent loss of genetic variation in wild populations since the industrial revolution. Evolutionary Applications 12:1505–1512.

- Funk, W. C., McKay, J. K., Hohenlohe, P. A., and Allendorf, F. W. (2012). Harnessing genomics for delineating conservation units. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 27:489–496.

- Hoban, S., Bruford, M. W., Funk, W. C., Galbusera, P., Griffith, M. P., Grueber, C. E., Heuertz, M., Hunter, M. E., Hvilsom, C., Stroil, B. K., Kershaw, F., Khoury, C. K., Laikre, L., Lopes-Fernandes, M., MacDonald, A. J., Mergeay, J., Meek, M., Mittan, C., Mukassabi, T. A., O’Brien, D., Ogden, R., Palma-Silva, C., Ramakrishnan, U., Segelbacher, G., Shaw, R. E., Sjögren-Gulve, P., Veličković, N., and Vernesi, C. (2021). Global commitments to conserving and monitoring genetic diversity are now necessary and feasible. BioScience 71:964–976.

- Landguth, E. L., and Cushman, S. A. (2010). Cdpop: A spatially explicit cost distance population genetics program. Molecular Ecology Resources 10:156–161.

- Landguth, E. L., Muhlfeld, C. C., and Luikart, G. (2012). CDFISH: An individual-based, spatially-explicit, landscape genetics simulator for aquatic species in complex riverscapes. Conservation Genetics Resources 4:133–136.

- Landguth, E. L., Bearlin, A., Day, C. C., and Dunham, J. (2017). CDMetaPOP: an individual-based, eco-evolutionary model for spatially explicit simulation of landscape demogenetics. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 8:4–11.

- Thatte, P., Joshi, A., Vaidyanathan, S., Landguth, E., and Ramakrishnan, U. (2018). Maintaining tiger connectivity and minimizing extinction into the next century: Insights from landscape genetics and spatially-explicit simulations. Biological Conservation 218:181–191.

- Day, C. C., Landguth, E. L., Bearlin, A., Holden, Z. A., and Whiteley, A. R. (2018). Using simulation modeling to inform management of invasive species: A case study of eastern brook trout suppression and eradication. Biological Conservation 221:10–22.

- Landguth, E. L., Holden, Z. A., Mahalovich, M. F., and Cushman, S. A. (2017). Using landscape genetics simulations for planting blister rust resistant whitebark pine in the US Northern Rocky Mountains. Frontiers in Genetics 8:1–12.