Guest Post by Brianna Rick, 2021-2022 Sustainability Leadership Fellow, and Ph.D. Candidate in the Department of Geosciences at Colorado State University

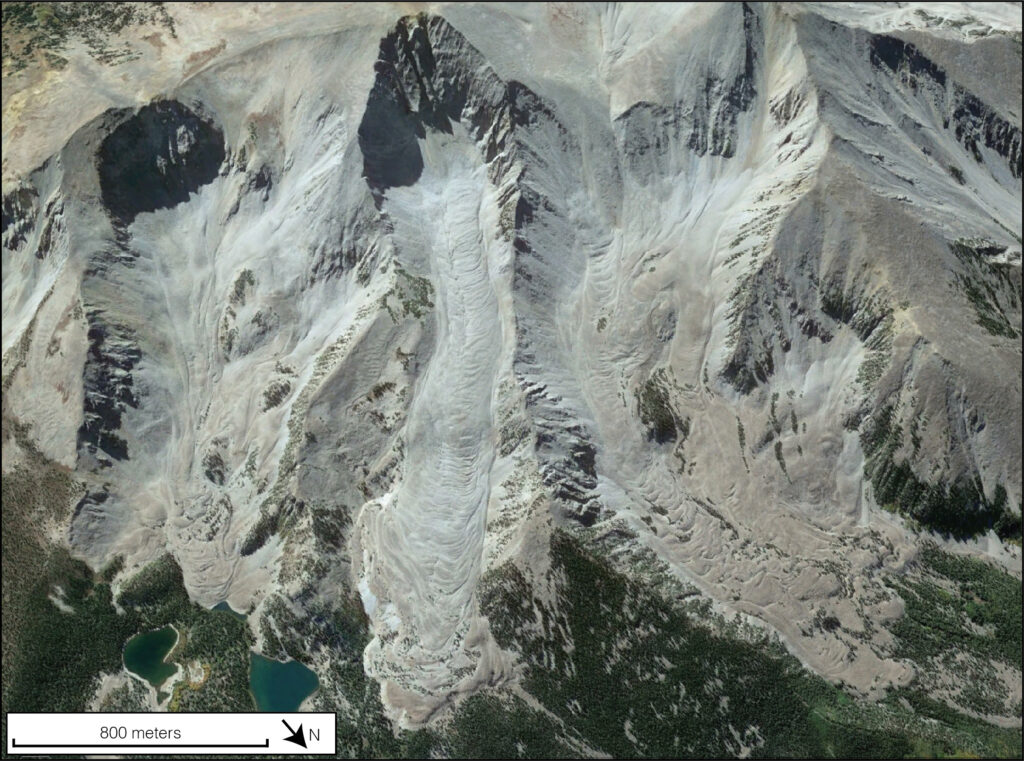

If you’ve ever been high up in the mountains in Colorado, it’s probable you’ve unknowingly encountered a rock glacier. From afar, these landforms look as though the side of the mountain is melting like an ice cream cone, or like a lava flow with no volcano to be found. Up close, they appear to be just another boulder field, unbeknownst to any traveler that ice is underfoot.

Colorado is home to over 3500 rock glaciers, often hiding in plain sight. When you think of a mountain glacier, you might imagine a large mass of white or blue ice, hanging in a cirque or flowing into a U-shaped valley. However, glaciers can be made of rock as well, or rather a combination of rock and ice. These “rock glaciers” can form when an ice glacier is buried with rock debris from surrounding slopes, or through a gradual process of many years of snowmelt freezing within a rocky slope until it starts to move downhill.

Although you may think of ice as a solid, it can flow slowly, such that glaciers are sometimes called “rivers of ice”. Rock glaciers move even slower than pure ice, averaging around 10 inches of movement per year in the Rocky Mountains. While ice-glaciers are susceptible to melt from direct sunlight and are affected by daily temperature changes, ice in rock glaciers can be found about 10 feet below the surface. These many feet of rock act as a blanket, shielding the internal ice from warming air temperatures. This allows rock glaciers to be resistant to climate warming, and provide refuge for species sensitive to increasing temperatures, from microbes to stoneflies to small mammals.

Rock glaciers vastly outnumber ice glaciers in Colorado, likely containing a far greater volume of ice, though receiving a fraction of the attention. Rock glaciers have long been ignored in conversations about water resources in the mountains, but have more recently gained attention for their unique benefits for cold-water creatures. These landforms can produce streams of near-freezing water in the late summer and fall, long after snow has melted. While they are usually low-flow streams, they may be large enough to retain diverse cold-water microbial communities.

The American pika (Ochotona princeps) is another animal that benefits from rock glaciers. Pikas are cute, small, rodent-like animals that depend on cold environments for survival. They can overheat and die at temperatures as low as 78° F. Pikas are losing habitat as the climate warms, which drives them upward to higher elevations to remain in cooler habitats. This warming threatens their existence when cooler, higher ground runs out, providing the pika a so-called “escalator to extinction”. Rock glaciers provide refuge for pikas by creating pockets of cool air between boulders, providing habitat that is continuously refrigerated by the ice buried below.

Rock glaciers are climate-resistant; however, they are not climate-immune. It is important to understand how much ice is present and how long these features may be able to supply streams and retain cold habitat to fully capture their ability to buffer certain species from climate demise.

Rock glaciers are abundant in the Rocky Mountains as well California’s Sierra Nevada, holding on to some of the last ice where ice glaciers can no longer be sustained. Alpine environments are warming at nearly twice the global average, in many areas creating environments inhospitable to surface ice. Rock glaciers and their blankets of rock provide a beacon of hope in a warming world for some of our most vulnerable species.

Next time you’re in the mountains, take a look around. You just might be in the presence of a rock glacier, a vital but undervalued component of Colorado’s alpine ecosystems.

————————————————

Curious whether your favorite hiking spot or next destination has a rock glacier nearby? Check out this interactive map to explore rock glacier locations in Colorado:

https://briannarick.github.io/dataviz/RGmap_Colorado.html

Resources:

Hotaling, S, Foley, ME, Zeglin, LH, et al. Microbial assemblages reflect environmental heterogeneity in alpine streams. Glob Change Biol. 2019; 25: 2576– 2590. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.14683

Johnson, G., Chang, H., and Fountain, A.: Active rock glaciers of the contiguous United States: geographic information system inventory and spatial distribution patterns, Earth Syst. Sci. Data, 13, 3979–3994, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-13-3979-2021, 2021.

Lusha M. Tronstad, Scott Hotaling, J. Joseph Giersch, Oliver J. Wilmot, Debra S. Finn “Headwaters Fed by Subterranean Ice: Potential Climate Refugia for Mountain Stream Communities?,” Western North American Naturalist, 80(3), 395-407, (5 October 2020)

Millar, C. I., & Westfall, R. D. (2010). Distribution and Climatic Relationships of the American Pika (Ochotona princeps) in the Sierra Nevada and Western Great Basin , U.S.A.; Periglacial Landforms as Refugia in Warming Climates. Arctic, Antarctic, and Alpine Research, 42, 76–88. https://doi.org/10.1657/1938-4246-42.1.76

Urban, M. C. (2018). Escalator to extinction. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(47), 11871–11873. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1817416115