By Nick VanLanen, 2018-2019 Sustainability Leadership Fellow and Ph.D. Candidate in the Ecosystem Science and Sustainability and the Graduate Degree Program in Ecology

The primary goal of wildlife management is to maintain healthy wildlife populations across the landscape. Wildlife managers strive to achieve this goal using multiple approaches, including setting harvest rates for game species, identifying and protecting critical habitat, controlling non-native species, moving individuals to unoccupied but suitable areas, or even actively altering the vegetation at a particular location. These approaches have resulted in some remarkable success stories; however, business as usual is likely to result in the severe loss of wildlife populations and species.

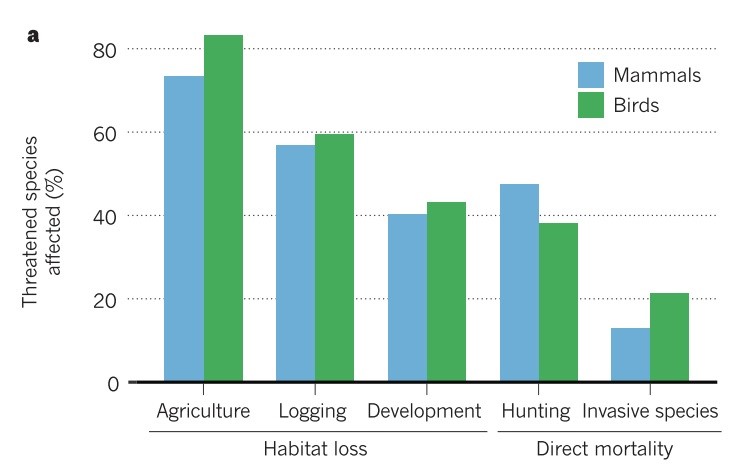

Despite our best efforts, the number of wildlife species threatened with extinction continues to increase each year. Today, approximately 30% of species assessed by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature are designated as threatened with extinction in the near future. Loss of native habitat is considered the primary threat to many of these species.

One seemingly obvious solution is to protect more native habitat; however, there can be severe unintended consequences to indigenous populations, local economies, and energy production when we do so. Due to these consequences and limited remaining natural landscapes, it is becoming increasingly difficult to protect new areas. This is resulting in some difficult decisions for wildlife managers because each species on the planet is thought to have unique habitat requirements, and frequently species’ needs directly conflict with each other.

Such is the case in the eastern United States where deciduous forests, logged decades ago, are now regrowing. This forest regrowth provides habitat for declining species which need mature forests, like the Wood Thrush. Unfortunately, there is now a scarcity of young forests which provide habitat for other declining species, like the Golden-winged Warbler. A similar situation is occurring across much of the western United States, where juniper and pine trees are being cut to enhance sagebrush habitat for the Greater Sage-grouse; an iconic species of the West. These cuts stand to negatively impact a suite of species, including the Pinyon Jay, which rely on the very trees being cut for sage-grouse. In these instances, there are declining species which require each type of habitat so which habitat should managers save and/or restore?

The need to manage for multiple wildlife species concurrently is not a new one. Managers have tried to shift from single-species management to managing for ecological health, intact systems, or the full ecological community for decades. Yet these attempts often focus on a single ecosystem. Now we are struggling to manage multiple ecosystems, despite habitat trade-offs for declining species with juxtaposed habitat requirements, when the total amount of natural space is limited. Given the complexity of nature, it has been difficult for managers to understand the impact of habitat management on a single species or ecosystem. It therefore seems a tall task to consider potential ramifications on other “non-target” species and systems as well.

Although the path forward seems daunting, we are better equipped than ever before to deal with this challenge. Improved climate, species distribution, and population models as well as landcover data from satellites provide us with valuable information regarding the amount, type, and location of habitat. Forecasts from these models can help predict what types of habitats may persist into the future. These models also provide critical information to develop forward-thinking landscape plans to address competing habitat needs for multiple species simultaneously.

Multi-species management has never been more complicated or important than it is today. By recognizing the complexity of this issue, and thinking about conservation in an increasingly integrated way, we can ensure that we leverage all the information and tools available to support native species. As we move forward, we need to encourage conservationists and managers alike to consider the long-term implications of management decisions, how changing landscapes and climate will impact species’ habitat into the future, and the full suite of species or communities which may be impacted by management. We also need to work across disciplines to incorporate predictions of where land-use will change across the landscape and determine the likely economic impacts of wildlife management on communities. Finally, we need to work across governmental agencies to integrate and coordinate management at regional scales.

There are early signs the field of wildlife management is changing. The development of partnerships like Joint Ventures provide opportunities for collaboration, synchronization, and integration of management efforts. These partnerships represent a great first step towards coordinated regional multi-species management. By working together, sharing knowledge, and considering multiple ecosystems we can ensure that wildlife management balances the needs of species and ecosystems, thereby providing a future with Greater Sage-grouse AND Pinyon Jays, instead of one or the other.