Guest Post By Lauren Hoskovec, 2020-2021 Sustainability Leadership Fellow and Ph.D. Student in the Department of Statistics

The air we breathe has a great impact on our health. If you’ve ever taken a trip to the mountains or deep in the forest, you probably know the invigorating feeling of taking a deep breath of fresh, clean air. Wouldn’t it be nice if all the air was like that?

When it comes to air pollution, a lot of factors are at play. Cars, industries, agriculture, and wildfires are among the top sources of air pollution. Ambient air pollutant levels are regulated at the national level by the EPA and some states have stricter standards. Just because there is a limit on air pollution doesn’t mean pollutant levels always fall within those limits, for example in the case of extreme wildfires. Further, the EPA doesn’t regulate indoor air pollution levels, which is where humans spend most of their time.

Many sources of air pollution provide benefits in other areas of life, so fighting for clean air can be tough. New research and technologies are tackling this problem with the innovation of electric cars, renewable energy, and green agriculture. These are promising fields, and it is in our best interest to devote resources to these advancements. In the meantime, how can we improve our personal air quality to promote better health and a cleaner local environment?

As mentioned before, humans spend most of their time indoors. This means if you’re in a house with a good air filter, that wildfire raging 20 miles away is not going to affect you nearly as much as if you walk outside. Small actions like replacing your air filter frequently during wildfire season can improve the health of everyone in your household. What other simple changes can you make?

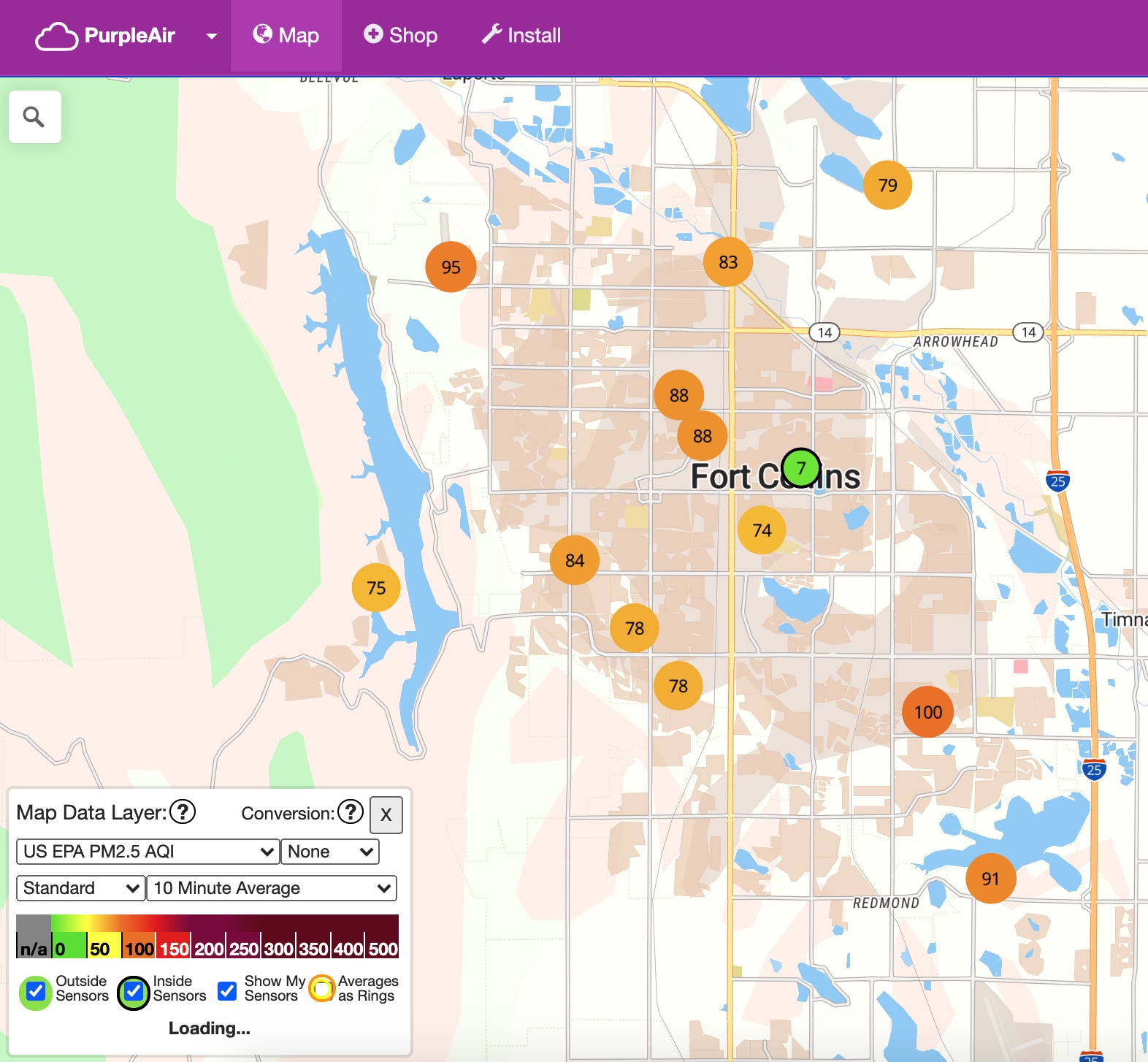

Many people are unaware of their exposure to air pollution and the associated risks. This came to my attention when the air quality index (AQI) in northern Colorado this summer was at high levels deemed unhealthy for outdoor exercise, yet dozens of little kids were still having soccer practice at the park. AQI is a concise measure of the amount of ozone and particulate matter in the air. This summer in Colorado, the AQI was often at an unhealthy level due to the devastating wildfires wreaking havoc in the National Forests. Air pollution exposure can have lasting effects on health, and mounting research is demonstrating the additional impact air pollution exposure can have on COVID-19 severity.

Exposure to air pollution might not be at the top of your list when you think of health. When it comes to leading a healthy lifestyle, the first items that come to mind are usually diet and exercise. To motivate behavior changes, companies like fitbit and Strava have developed devices and apps to measure individual fitness. Smart watches track activities such as steps, minutes of exercise, and sleep in the hopes of providing you with the information to make positive changes to your lifestyle. Apps like Strava allow you to compare your activity with others, motivating those with a competitive edge. What if there was a similar type of app for air pollution exposure?

Lightweight personal air quality monitors are currently being engineered to track individual exposure to air pollution (see Good et al. 2016 and Koehler et al. 2019 for details on how these monitors have been used). These wearable devices record your exposure to air pollution wherever you go. In addition, new statistical models, such as the one I am developing for my PhD research, can analyze time-resolved air pollution exposure data among multiple individuals. These models search for shared patterns among individuals to identify combinations of location, activity and environment that result in similar levels of air pollution exposure.

Can we combine personal exposure monitors and new statistical tools in a personal air quality app? This could increase air quality awareness and perhaps motivate people to make individual changes to protect their health. Not only that, combining information from hundreds or thousands of users could identify hot spots of air pollution within a community. As light is shed on activities that expel large amounts of pollutants, people may turn away from harmful industries and support cleaner solutions, spurring green innovation. Educated individuals taking collective action for a healthier environment can have a faster impact than waiting for technological breakthroughs or policy changes.

Solutions to sustainability are numerous, but many are slow to occur due to competing interests. By leveraging tools such as apps, personal exposure monitors, and advanced statistical methods, we can equip individuals with knowledge about their exposure to air pollution to make personal choices for better health and a cleaner environment.

References

Good, N., Molter, A., Ackerson, C., Bachand, A., Carpenter, T., Clark, M. L., Fedak, K. M.,Kayne, A., Koehler, K., Moore, B., L’Orange, C., Quinn, C., Ugave, V., Stuart, A. L., Peel, J. L., and Volckens, J. (2016). The Fort Collins Commuter Study: Impact of route type and transport mode on personal exposure to multiple air pollutants. Journal of Exposure Science and Environmental Epidemiology, 26(4):397–404.

Koehler, K., Good, N., Wilson, A., Molter, A., Moore, B. F., Carpenter, T., Peel, J. L., and Volckens, J. (2019). The Fort Collins commuter study: Variability in personal exposure to air pollutants by microenvironment. Indoor Air, 29(2):231–241.