By Sheena Martenies, 2018-2019 Sustainability Leadership Fellow and Postdoctoral Fellow in the Department of Environmental and Radiological Health Sciences

If you aren’t currently reading this while riding along on a major highway, sitting across the street from a large industrial facility, or gazing out across the wide expanse of an active wildfire, do me a favor a take a large, deep breath of air. Now breathe out. Thanks to the Clean Air Act, that breath of air you just took is reasonably clean. But that doesn’t mean that we still don’t have work to do to improve air quality in the United States. And it definitely doesn’t mean we should stop talking about air quality in the United States, either.

The Clean Air Act (CAA) is a broadly successful environmental policy that has sparked a tremendous amount of research into the health effects of air pollution. Over the last 40+ years, thousands of studies have identified a range of health effects from ambient air pollutants, ranging from missed days of work and days with mild respiratory symptoms all the way up to premature death from cardiovascular disease or cancer. This expansive and well-characterized body of research has helped environmental policy makers clean up our air. Given that recent polls suggest many Americans are largely unaware of specific health effects of climate change, it could also be immensely valuable to scientists and advocates trying to encourage people to adopt climate-friendly policies.

Though some make think of efforts to address air pollution and climate change as relatively recent issues, we’ve actually been regulating air pollution in the US for more than 50 years. Since the industrial revolution, when humans figured out how to replace horses and human labor with engines, we’ve been generating large volumes of air pollution. By the 1950’s, the air in the United States was so polluted that people started to demand action from Congress. In 1970, President Nixon signed the Clean Air Act Amendments into law. The updated law formally required the federal government to establish the National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS; pronounced “nacks”). President Nixon also established the Environmental Protection Agency by executive order to oversee the implementation of these standards. In 1990, the CAA was amended again to include many of the features we’re familiar with today, including the acid rain program.

The Clean Air Act regulates six conventional (or common) air pollutants: particulate matter, ozone, nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide, carbon monoxide, and lead. These pollutants are often called “criteria” air pollutants because the EPA was originally charged with identifying criteria in order to designate them as harmful to human health. The two most important conventional air pollutants for health are ozone and fine particulate matter (suspended solid particles or liquid droplets that are generally less than 1/20th the width of a human hair in size). Ozone is formed in the atmosphere when nitrogen dioxide generated by combustion (e.g., car engines and fires) mixes with volatile organic compounds (e.g., evaporated gasoline or the solvents in household paint) in the presence of sunlight. Fine particulate matter can be emitted directly by sources, such as a smokestack at a power plant, or they can be formed in the atmosphere as a secondary pollutant. Regulation of these pollutants requires US EPA to regularly review the hundreds of studies published every year to identify which adverse health effects are caused by air pollution.

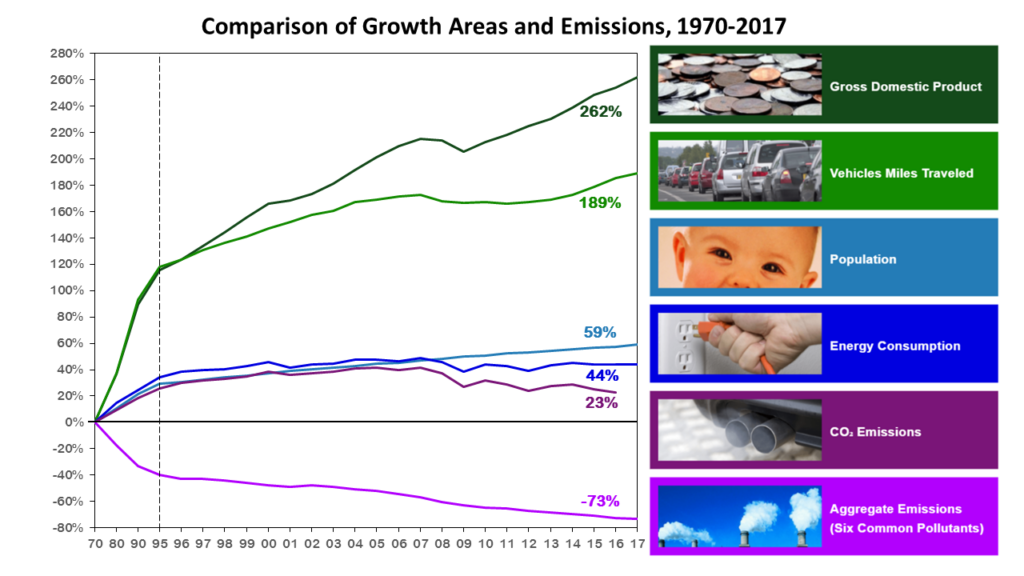

Through several programs designed to lower emissions of these pollutants, the CAA has been able to improve air quality in the United States. Since 1970, the amount of air pollutants released into the atmosphere has decreased more than 70%. But even though we’ve come a long way in terms of air quality since early days of the Clean Air Act, ambient air pollution still has a substantial burden on people living here in the United States and across the globe. Here in the US, particulate matter and ozone are responsible for almost 135,000 premature deaths each year, primarily among older adults. Globally, outdoor particulate matter is the leading environmental cause of death, with outdoor particulate matter and ozone causing for more than 4.3 million premature deaths each year. In comparison, 6.3 million people die each year from smoking. Many of these air pollution-related deaths could be prevented with more carefully crafted environmental policies.

But these conventional pollutants aren’t just a health problem—they’re also a climate change problem. Many of the same sources that generate these harmful air pollutants (including cars and trucks, industrial facilities, coal-fired power plants, and natural disasters like wildfires) also contribute to the rising level of CO2 in the atmosphere that are driving climate change. For example, using carbon-based fuels to generate electricity or power our vehicles produces a substantial amount of CO2, the primary pollutant responsible for climate change. This combustion also produces nitrogen dioxide, which causes a wide range of respiratory effects, including asthma attacks. When this pollutant enters the atmosphere, it reacts with other pollutants such as ammonia to generate fine particulate matter, which can cause a number of adverse health effects, including heart attacks and premature death.

In general, Americans are generally aware that climate change will impact health, but less than one third are able to name a specific health effect from climate change. There also appear to be important political and generational divides. Older Americans and Americans who lean Republican are less likely to be concerned with climate change as younger Americans and Americans who lean Democrat or are independent voters. However, a majority of Americans believe that regulations are necessary to increase reliance on renewable energy to reduce air pollution, suggesting there is a disconnect between air pollution and climate change. Effective messaging around policies to support, for example, renewable energy policies should incorporate information that skeptical audiences are more likely to believe and accept. This messaging would benefit from including information on the well-known effects of conventional air pollutants that come from the same sources as greenhouse gases—conventional pollutants often have the largest effects on older adults and people with preexisting respiratory and cardiovascular disease.

Climate change messaging often focuses on the environmental consequences of burning fossil fuels, but there are also well documented (and well researched!) public health consequences to burning carbon-based fuels for energy. This type of information could prove useful in combating some of the uncertainty around climate change effects. There are a great number of broad but potentially uncertain health effects of a changing climate, and this uncertainty can sometimes be difficult to communicate to skeptical audiences. However, we can leverage the well characterized literature on the health effects of these conventional pollutants to strengthen our public health and climate change messaging and better connect the consequences of climate change to people on a personal level. It may be far easier to relate to the consequences of increased exposures to particulate matter for someone with asthma or cardiovascular disease that it would be to the less-certain consequences of rising sea levels. As an added bonus, these messages can be spread without mentioning “climate change” at all, which may help reach audiences that are tired of hearing about human-caused effects on the climate.

Overall, air quality in the US has improved tremendously since the 1970’s, but that doesn’t mean our work is done. Americans are driving more, living in more densely packed urban centers, and consuming energy at ever-increasing levels. All of these factors will contribute to the generation of conventional and climate change pollutants that will have serious immediate and long-term health consequences. Policies that reduce the use of carbon-based fuels will simultaneously reduce both greenhouse gas and conventional pollutants, leading to real improvements in public health. But implementing these policies will require more Americans to buy into the idea that climate change is a threat to human health. By drawing on the large body of evidence that conventional air pollutants are harmful, climate change scientists and environmental advocates can broaden their messaging efforts and encourage more Americans to support the types of policies that will address climate change.

Sources:

Brenan M, Saad L. 2018. Global Warming Concern Steady Despite Some Partisan Shifts. Gallup.com. Available: https://news.gallup.com/poll/231530/global-warming-concern-steady-despite-partisan-shifts.aspx [accessed 16 November 2018].

Fann N, Lamson AD, Anenberg SC, Wesson K, Risley D, Hubbell BJ. 2012. Estimating the National Public Health Burden Associated with Exposure to Ambient PM2.5 and Ozone. Risk Analysis 32:81–95; doi:10.1111/j.1539-6924.2011.01630.x.

Funk C, Kennedy B. 2017. U.S. Public Divides Over Environmental Regulation and Energy Policy. Available: http://www.pewinternet.org/2017/05/16/public-divides-over-environmental-regulation-and-energy-policy/ [accessed 16 November 2018].

Gakidou E, Afshin A, Abajobir AA, Abate KH, Abbafati C, Abbas KM, et al. 2017. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 84 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. The Lancet 390:1345–1422; doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32366-8.

Maibach EW, Kreslake JM, Roser-Renouf C, Rosenthal S, Feinberg G, Leiserowitz AA. 2015. Do Americans Understand That Global Warming Is Harmful to Human Health? Evidence From a National Survey. Annals of Global Health 81:396–409; doi:10.1016/j.aogh.2015.08.010.

National Research Council. 2004. Air Quality Management in the United States. National Academies Press: Washington, DC.

Popovich N, Schwartz J, Schlossberg T. 2017. How Americans Think About Climate Change, in Six Maps. The New York Times, March 21.

Reinhart R. 2018. Global Warming Age Gap: Younger Americans Most Worried. Gallup.com. Available: https://news.gallup.com/poll/234314/global-warming-age-gap-younger-americans-worried.aspx [accessed 16 November 2018].