By Trevor Even, 2018-2019 Sustainability Leadership Fellow and Ph.D. Student in the Department of Anthropology and the Graduate Degree Program in Ecology

Whether you are working toward developing more sustainable practices within industries, working with communities to develop climate change adaptation strategies, or working alongside government officials to mitigate risks and develop policies, understanding the local-level realities of the people you hope to help is job one. Without understanding how people live, what they want, what they care about, and how the various risks they face shape their daily experiences, efforts to improve conditions – whether through technology, practices, or policy – are likely to face serious setbacks, being at best ham-fisted, and at worst, total failures. However, wading into local conversations about complex topics of livelihoods, climate, land use, and water management is no meager task. As a result, there is a need for social scientists and others to connect broader conversations about sustainability and climate change action to the diverse on-the-ground realities that people around the world experience.

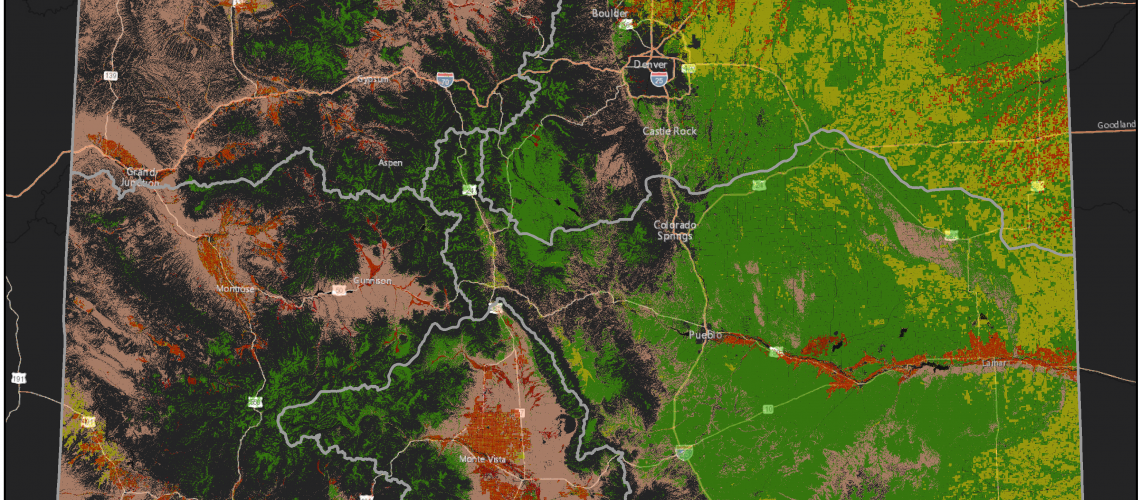

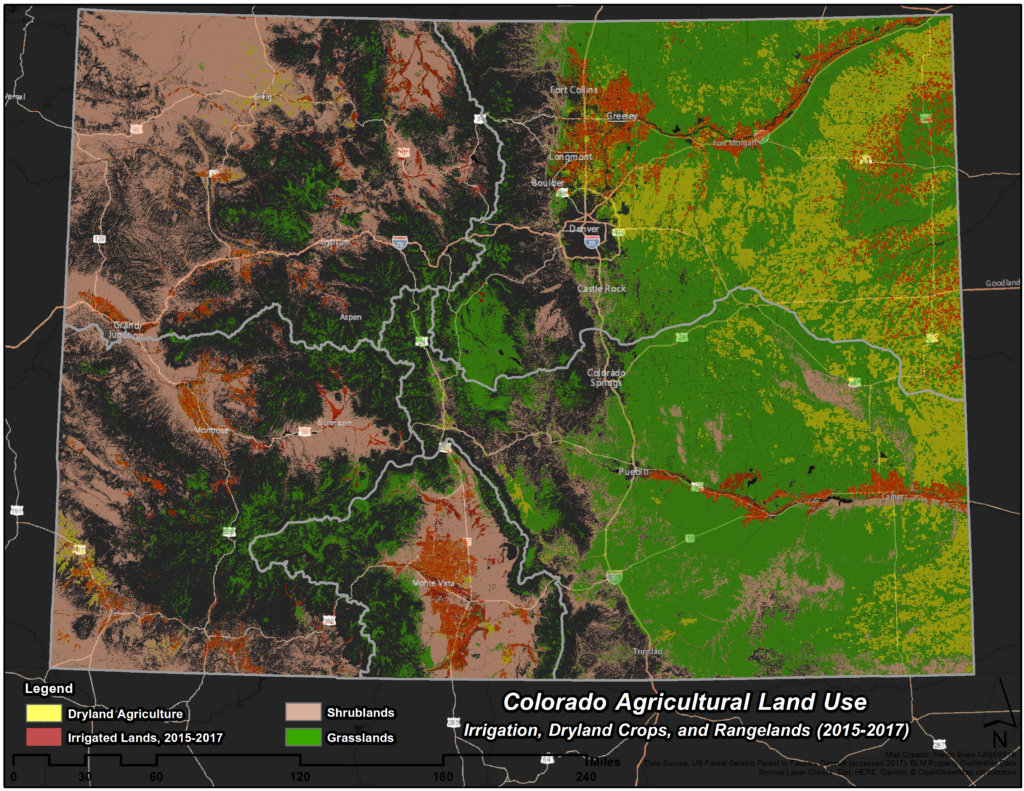

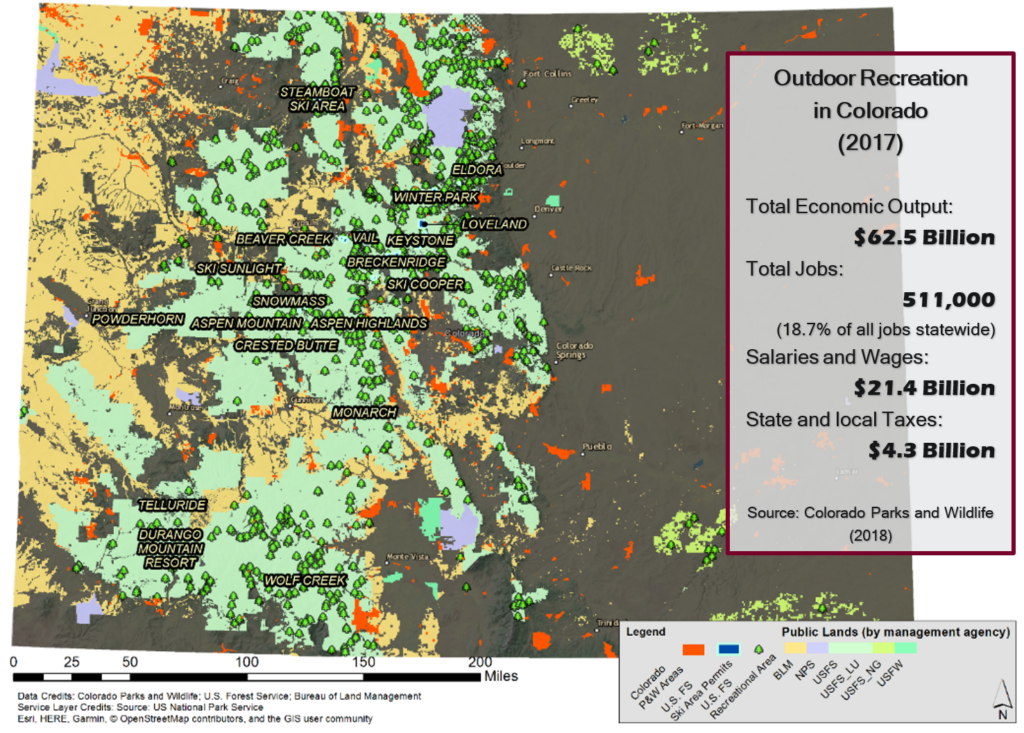

It is with this thinking in mind that I and my advisor, Dennis Ojima, have been working over the past year to develop a somewhat unusual report, due to be released in the coming weeks: titled Changing Weather and Livelihoods in Rural Colorado, it attempts to bring together the variety of local-level stories that are being told within the state’s diverse rural communities on how recent shifts in global climate are manifesting themselves as changes in local weather patterns, and what this means for people attempting to make a living off of the land. Based on conversations with leaders in the recreation, agriculture, and public lands management fields (all of which play a powerful role in rural areas of the state), local media reports, and previous Colorado-focused scientific research, our goal is to provide decision-makers at multiple levels – as well as concerned members of the general public – with a grounded understanding of what large scale issues like changes in weather patterns are already meaning for people whose livelihoods bring them into close contact with the state’s broad array of ecosystems, landscapes, and micro-climates. To do this, we focus on the ranching, farming, and outdoor recreation sectors, specifically, looking at both stories of impacts from recent extreme weather events as well as novel approaches to land use, management, and community organization that are being mobilized in response to these impacts.

Like many places across the Western United States and other semi-arid regions of the world, shifts in weather patterns associated with global climate change are already expressing themselves in Colorado in a variety of ways, both subtle and catastrophic, be it in the form of longer, more intense, and more destructive wildfire seasons, extended drought conditions, extreme storms, or the amplification of existing pressures related to human population growth. As a result, people from a wide range of cultural backgrounds are finding themselves forced to come to grips with what an increasingly unpredictable “normal” means for their well-being. Indeed, as temperatures have risen over the last several decades, the state’s largely winter-moisture-dependent ecosystems and landscapes are already showing signs of increasing strain, be it from more rapid losses of soil moisture following rainfall, more rapid melting of snowpack in the spring, and massive tree mortality due to invasive insects (see Gordon and Ojima, 2015 for more detailed information about recent climate change impacts in Colorado; Lukas et al. 2014 for analysis of historical climate trends) . Given, then, that Colorado is a state where water supplies are already heavily over-allocated, these climate-driven factors are also bringing significant pressure to bear on both the complex water management systems found across the state and the economic systems that rely upon them, with the potential to leave existing ways of life untenable as temperatures continue to rise and precipitation patterns become more volatile in the years to come.

And while the region’s growing cities face a variety of challenges (and will no doubt play a central role in future battles over the state’s limited water supplies), these risks are most potent in the state’s numerous rural and mountain communities, many of which rely heavily upon what are referred to as “land-based livelihoods.” Including things like farming, ranching, outdoor recreation services, hunting, fishing, and others, land-based livelihoods differ notably from more prototypically urban livelihoods found in the information, finance, or technology sectors in that they rely upon direct interaction with both natural ecosystems and outdoor weather as a normal part of their operation. And much as public health researchers have observed regarding outdoor workers in urban areas, people engaged with land-based livelihoods can serve as a sort of “canary in the coal mine” when it comes to understanding how the various signals of a warming world get translated into impacts on well-being and insults to socio-ecological system arrangements. Because of this, however, they also represent a vanguard of adaptation, both in terms of specific practices within industries and the broader development of pathways toward community-level learning and action. As such, they form a critical area of investigation for those hoping to write the larger story of humanity’s transition toward more sustainable human-environment interactions.

What we find in our exploration of these issues, then, is a network of rural communities in numerous states of transformation – both willful and regretted – as the ecosystems that they rely upon shift in response to both increased pressure from human use and transitions toward a warmer and more unpredictable climate. For example, in the San Luis Valley, located in the south-central region of the state, local farmers have found that dwindling groundwater supplies are no longer enough to provide for historical agricultural production methods as nearly twenty years of below-historical-average soil moisture levels drag on (see Cody et al. 2015). In response, they have begun implementing a novel system for groundwater withdrawal management, with private water right owners entering into a valley-wide water banking system and lowering withdrawals in response to community reports and climate data. Similarly, in the state’s many ski towns, increasing amounts of money are being spent mitigating the loss of snowpack through artificial means, and city councils and business coalitions are attempting to diversify local economies away from purely winter-dependent incomes as the season rapidly shortens and warm-weather conditions become more common. Some ski towns are also taking on a growing role in forest and river stewardship, working to maintain local environments as insect epidemics and high temperatures threaten to dramatically transform cherished landscapes and streams. Some farmers and ranchers, also taking stock of increasingly fragile ecosystems, are implementing increasingly sophisticated methods of landscape management, both for improved soil health and wildlife habitat. However, in other areas, losses from wildfires, flooding, and extreme weather impacts have left many households and communities with seemingly few options as the vulnerabilities of increasingly aged and often impoverished rural areas see growing costs from disaster events. Indeed, as pressures from international market instabilities for agricultural products, demographic losses as young people move more and more to cities, and failing social service systems all converge, shifts in climate may force many rural communities into permanent decline.

With global action to mitigate climate change stagnating and, in places like Brazil and the United States, reversing course amid a convergence of regulatory capture, bald-faced ignorance, and a toxic mix of cynicism and stupidity, the need for scientists and researchers to find ways to more effectively advocate and promote shifts towards more sustainable and adaptive practices only grows. One of the most important dimensions of this, however, lies in helping policy-makers, researchers, engineers, and other “outsiders” in the adaptation world gaining a better understanding of how local communities that are impacted by the effects of climate change and other unsustainable conditions understand and respond to the realities they are facing, and what it is that those communities actually need to pursue their desired outcomes. Put another way: without understanding the local-level stories that people are already telling about the situations they are living in, we will have a hell of a time trying to change the trajectories of those stories’ characters. Similarly, without understanding the conversations that people are already having, it is difficult to begin a new one about the changes to local and state level institutions that sustainable transformations will likely require. As such, while it is critical that we continually take stock of how phenomena at state, regional, and broader scales interact with local phenomena, we must ground ourselves first in these local perspectives when working in settings where we hope to apply sustainability and adaptation science.

At a deeper level, however, what this report ultimately finds is that the most basic – and potentially powerful – means of adaptation and action comes in the form of communities learning to work together to address shared problems. As a result, efforts to bring about change will have to work in ways that integrate themselves in the experiences, plans, goals, and relationships that are already at play in local communities. Because of this, our group hopes to turn more attention to these local level views and values in our on-going research, which will drill down on issues of water and the varied futures envisioned by different water system actors across the South Platte Basin, where much of the state’s population and water use transpires. More importantly, we hope that this work will enable us to begin a more diverse conversation on issues of sustainability and climate action across the state as we release the report to various statewide agencies, reporters, and other collaborators.

If you are interested in finding out more about our work, or the forthcoming report, contact me at trevor.even@colostate.edu.