By Rachel Buxton, 2017-2018 Sustainability Leadership Fellow and Postdoctoral Fellow in the Department of Fish, Wildlife, and Conservation Biology

Imagine yourself in your favorite park, looking out over an expansive wilderness. You close your eyes and take in the natural quiet – the wind rustling the leaves, a nearby babbling brook, and birds singing from the trees. We’ve only now started to understand the importance of these natural sounds and the collective ‘soundscape’ they create. For humans, natural soundscapes restore our senses: reducing stress, increasing our ability to concentrate, and improving mood1. Most animals rely, at least in part, on sound to carry out essential activities such as finding and avoiding becoming food2. Unfortunately, these natural sounds are increasingly under threat.

What is a soundscape?

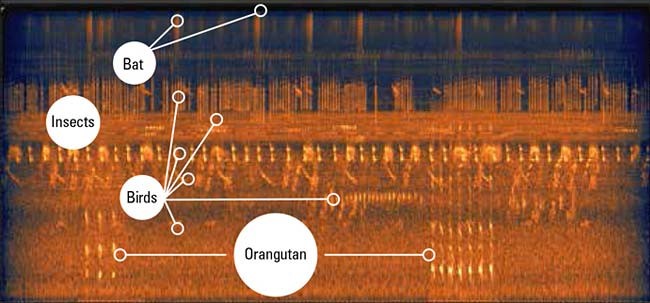

Each landscape has its own unique set of sounds. These soundscapes include a variety of geophysical sounds, such as ocean waves and thunder storms. This is accompanied by the sounds that animals produce for communication, from wolves howling to frogs calling. Animals produce and listen for these acoustic signals to defend territories, attract mates, deter predators, navigate, find food, and maintain social groups. In the same way that animals eat particular food and use specific habitat to avoid competition with other species in an ecosystem, animals use a specific part of the acoustic environment to avoid overlapping sound signals3. For instance, birds with songs at a similar pitch will stagger their songs so as not to sing at the same time. Thus, each species occupies what is known as an ‘acoustic niche’.

When habitats are disturbed, the acoustic environment is thrown off balance, altering the natural partitioning of acoustic space. For example, an invasive species that sings at the same pitch as a native species may cause ‘acoustic competition’, in which acoustic communication among native species is degraded by the sounds produced by an invader5. Also, human produced sound, such as traffic and machinery noise, has become widespread, causing disruption of the acoustic environment at enormous scales6.

What is noise pollution?

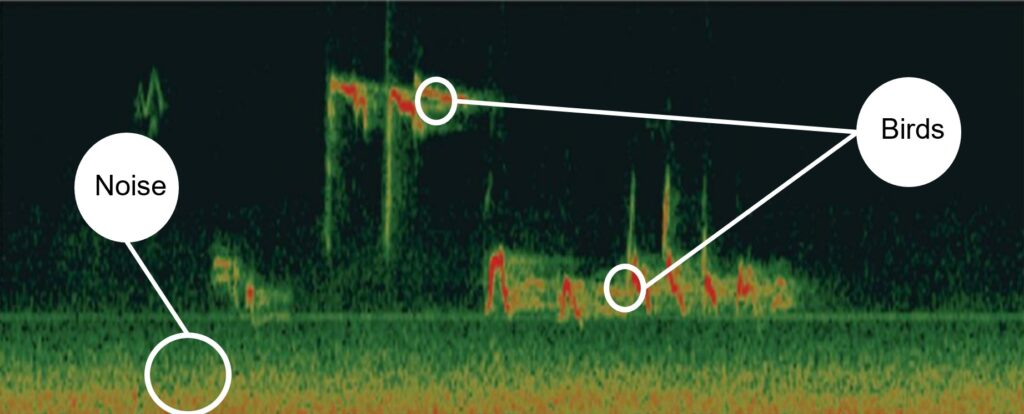

“Noise” is an unwanted or inappropriate sound. Human sources of noise in natural environments include sounds from aircraft, roads, machinery, or industrial sources. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, noise pollution is noise that interferes with normal activities, such as sleeping and conversation, and disrupts or diminishes our quality of life8.

How much of a threat is posed by noise pollution?

Noise pollution interferes with natural soundscapes by masking natural sounds. In other words, important natural sounds are either no longer audible or severely degraded by overlapping human produced sound. For humans, noise pollution degrades the calming effect that we feel when visiting natural areas and listening to natural sounds. For wildlife, the inability to hear acoustic signals can disrupt essential life processes and can mean the difference between life and death for many species9. In turn, noise pollution alters ecological communities. For example, reduced hunting success of carnivores can result in inflated numbers of prey species such as deer.

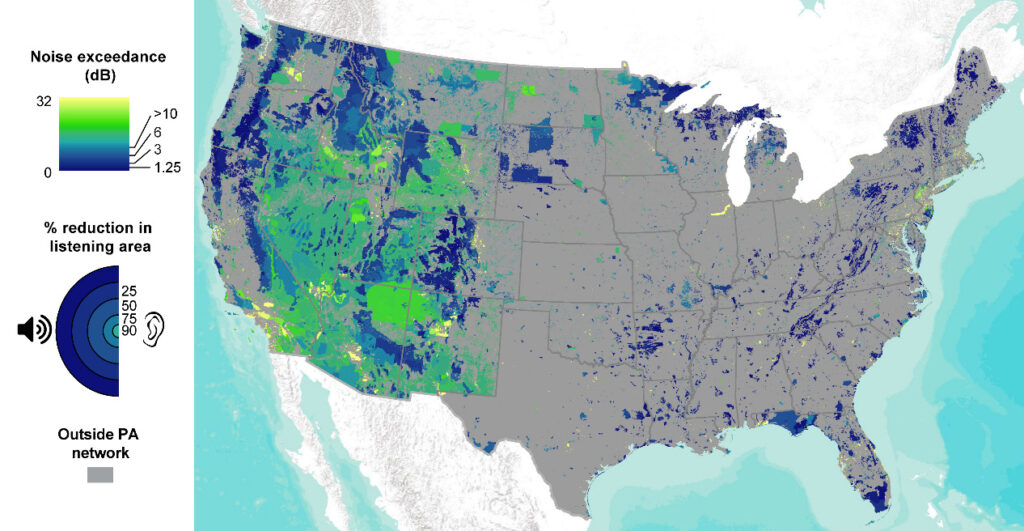

As transportation networks, resource extraction, motorized recreation, and urban development continue to grow, human produced noise has become ubiquitous. In the United States, noise pollution has altered soundscapes in even the most remote protected areas. A recent study found that although wilderness areas – places that are preserved in their natural state, without roads or other development – generally experience near-natural sound levels, 12% experienced noise pollution that doubled sound energy6. Noise pollution at these levels results in a 50% reduction in the distance at which natural sounds can be heard. Wilderness areas are managed to minimize human influence, so most noise sources come from outside their borders.

How do we protect natural soundscapes?

Strategies to reduce noise in protected areas include establishing quiet zones where visitors are encouraged to quietly enjoy protected area surroundings, and confining noise corridors by aligning airplane flight patterns over roads. Thus, unlike less tractable threats, like climate change, we have the tools to take action and control noise pollution now.

Protecting natural acoustic environments is important to protect wildlife and so that people can still enjoy the sounds of birdsong and wind through the trees.

References

1Gould van Praag CD, Garfinkel SN, Sparasci O, Mees A, Philippides AO, Ware M, Ottaviani C, and Critchley HD. 2017. Mind-wandering and alterations to default mode network connectivity when listening to naturalistic versus artificial sounds. Scientific Reports 7:45273.

2Brumm H. 2013. Animal communication and noise. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany.

3Pijanowski BC, Villanueva-Rivera LJ, Dumyahn SL, Farina A, Krause BL, Napoletano BM, Gage SH, and Pieretti N. 2011. Soundscape ecology: the science of sound in the landscape. Bioscience 61:203-216.

4Servick K. 2014. Eavesdropping on ecosystems. Science 343:834-837.

5Both C, and Grant T. 2012. Biological invasions and the acoustic niche: the effect of bullfrog calls on the acoustic signals of white-banded tree frogs. Biology Letters 8:714-716.

6Buxton RT, McKenna MF, Mennitt DJ, Fristrup KM, Crooks K, Angeloni LM, and Wittemyer G. 2017. Noise pollution is pervasive in U.S. protected areas. Science 356:531-533.

7Zwart MC, Dunn JC, McGowan PJK, and Whittingham MJ. 2016. Wind farm noise suppresses territorial defense behavior in a songbird. Behavioral Ecology 27:101-108.

8https://www.epa.gov/clean-air-act-overview/clean-air-act-title-iv-noise-pollution

9Simpson SD, Radford AN, Nedelec SL, Ferrari MCO, Chivers DP, McCormick MI, and Meekan MG. 2016. Anthropogenic noise increases fish mortality by predation. Nature Communications 7:10544.